The Witch of West Nyack

“This neighborhood has the doubtful honor of having been the scene of the last trial for witchcraft held in New York State, possibly the last among a so-called civilized people.”

-The History of Rockland County, by Frank Bertangue Green

Think of witches and Salem, Massachusetts comes to mind. But Sleepy Hollow Country has its own including Hulda the Witch of Sleepy Hollow and Jane Kanniff, the alleged witch of West Nyack.

In the hamlet of West Nyack, six miles from Sleepy Hollow as the raven flies, is a historic marker at the site of the last witch trial in New York State. Some versions of her story use the name Hannah instead of Jane, others recall local Dutch farmers referring to her as “Naut” Kanniff, a salutation of unknown meaning and origin. Whatever her given name, descriptions of Kanniff are invariably cartoonish. Like so many accused witches, Kanniff was a marginalized person living on the edge of society.

In early 1815 or 1816 Clarksville, as the hamlet was known then, nearly everyone was bound by ties of blood and marriage. Any newly arrived stranger became the subject of gossip and rumor. Jane almost invited suspicion. Twice widowed, she was an aged woman living in an unpainted, rickety house with her only child, a black cat and talking parrot. Unlike her plainly dressed neighbors, she favored bold colors and wore her hair in unconventional ways and led a mostly solitary existence. From her deceased husband, a Scottish physician, Kanniff had learned enough of herbalism to concoct effective cures for mild maladies. Adding to the matter, the son, Tobias Lowrie, was as eccentric and antisocial as his mother.

“From her deceased husband she had gathered a smattering of medicine, and now, when placed where she could get at the herbs known in her Materia Medica, she made wondrous decoctions with which she treated such as came to her for aid, and I have been informed by those who knew her, with most excellent results.”

-The History of Rockland County, by Frank Bertangue Green

There was no single act that provoked the witch trial. Rather, it was the accumulation of suspected misdeeds that turned the community against her. Local house wives finding it difficult to churn a proper butter would discover, upon emptying the churn, a horseshoe branded into the bottom. A prominent member of the local church passed a sleepless night due to the incessant lowing of his milk herd. At daybreak he found his best milk cow inexplicably standing in a farm wagon. From that time forward she yielded no milk.

Never mind that a little heat on a cold morning would help butter to set, or that the farmer’s dog was known to harass his own cattle. The cause must surely be witchcraft and all eyes turned toward Jane Kanniff.

A later historian surmised that neither a legally appointed judge nor the dominie of the local Reformed Church would do anything but laugh at such a charge. Suspecting as much, the local citizens surreptitiously took the law into their own hands. Only upstanding citizens, of course, would be allowed to act on such a serious charge as witchcraft, resulting in nomination of the resident physician for judge and a jury of neighborhood farmers. In the early 1800s medical practice was a far cry from today’s industrial medicine. Was the physician “judge” truly impartial or perhaps swayed against competition from a more competent female practitioner?

The good citizens held a secret meeting at Pye’s wool mill at which they decided the test would be the ancient practice of dunking, in which the alleged witch is bound hand and foot and thrown into a body of water. In earlier times in Western Europe and America, an alleged witch who floated would be found guilty of witchcraft and executed. If the alleged witch sank and drowned, the innocence of the unfortunate defendant would be beyond doubt. Guilty or innocent, the accused did not survive “trial”.

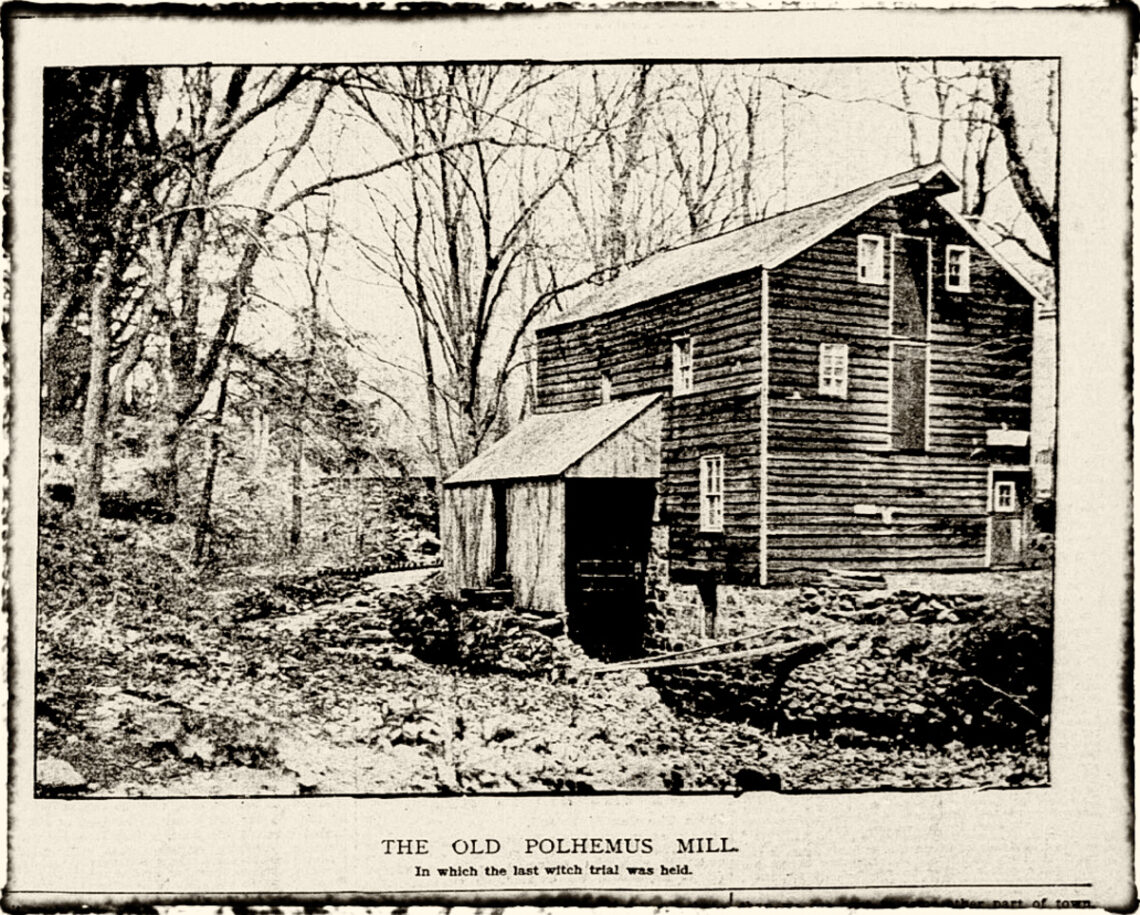

Kanniff was apprehended, bound hand and foot, and carted off to the nearest pond. But before she was cast into the water, a separate group of locals happened upon the gathering. Other counsel prevailed and instead of the water test the jury decided to use the enormous flour scales at Auert Polhemus’s grist mill to weigh Kanniff against a bible.

This was no church-pew bible weighing a couple pounds. This was a Dutch family Bible with a capital “B”. The great book was itself huge, covered with wood boards and bound in iron with an iron carrying chain. If outweighed by such a hefty tome, she would be a witch beyond doubt and suffer accordingly. Against her vociferous protest, Kanniff was put in the scales and weighed.

Writing in 1886, Frank B. Green dryly observed “Weighing more than the Bible, the committee released her, amid the ominous shaking of heads at the decision of her judges. Her persecutors were threatened with an action at law.” Kanniff was released, ending the inglorious last witchcraft trial in New York State.

Or did it end there? A short time later one of Pye’s children is alleged to have met a gruesome fate at the wool mill where the committee had first plotted the witch trial. Through some accident a large wooden hammer weighing hundreds of pounds and used for beating out wool cloth fell on the child, crushing him beyond recognition. This was, of course, attributed to Jane Kanniff for her brutal treatment at the hands of her churchy neighbors.

Nothing remains today of the Polhemus mill, formerly the De Clark mill at the southwest corner of Germonds Road and Strawtown Road. Just a historic marker noting its historic significance as the site of the last witch trial in New York State.

Burial of the Witch of West Nyack

The late John Scott, Historian Emeritus of The Historical Society of Rockland County, identified the Kanniff home as a small wooden, unpainted building just above the burial ground adjoining the old Dutch meeting house on Germonds Road. While Jane Kanniff’s date of death and grave are lost to history, the most plausible local legend is that she was interred in that burial ground adjacent to her residence. Known today as Clarkstown Reformed Church Cemetery, no grave marker for Jane survives.

Recent accounts alternately place Kanniff at the Germonds Presbyterian Cemetery. While this burying ground had roots in the local Dutch community—it was established as the Dutch Evangelical Church of Clarksville—its founding in 1860 does not seem to fit the timeframe of the witch trial 44 years earlier.

Jane Kanniff, the alleged witch of West Nyack, purportedly lived in a weathered old house above the Old Clarkstown Reformed Church. Organized in 1750, the church was rebuilt in 1826. It burned in 1904. Kanniff was allegedly buried in the church’s cemetery on Germonds Road. Near the burial ground is a bronze tablet on a red sandstone pillar marking the former location of the church.

Alternate accounts place Kanniff’s burial location a mile away at the Germonds Presbyterian Cemetery. Since the Germonds church was founded in 1860, this seems unlikely.

The Clarkstown Witch – The Operetta

On August 8, 1958 the United States Congress established the Hudson-Champlain Celebration Commission “to develop and execute suitable plans for the celebration, in 1959, of the three hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the exploratory voyages in 1609 of Henry Hudson and Samuel de Champlain”. In his proclamation of the celebration, President Dwight Eisenhower encouraged schools, patriotic and historical societies, and civic and religious organizations to participate in the commemoration through appropriate ceremonies, celebrations, and festivals.

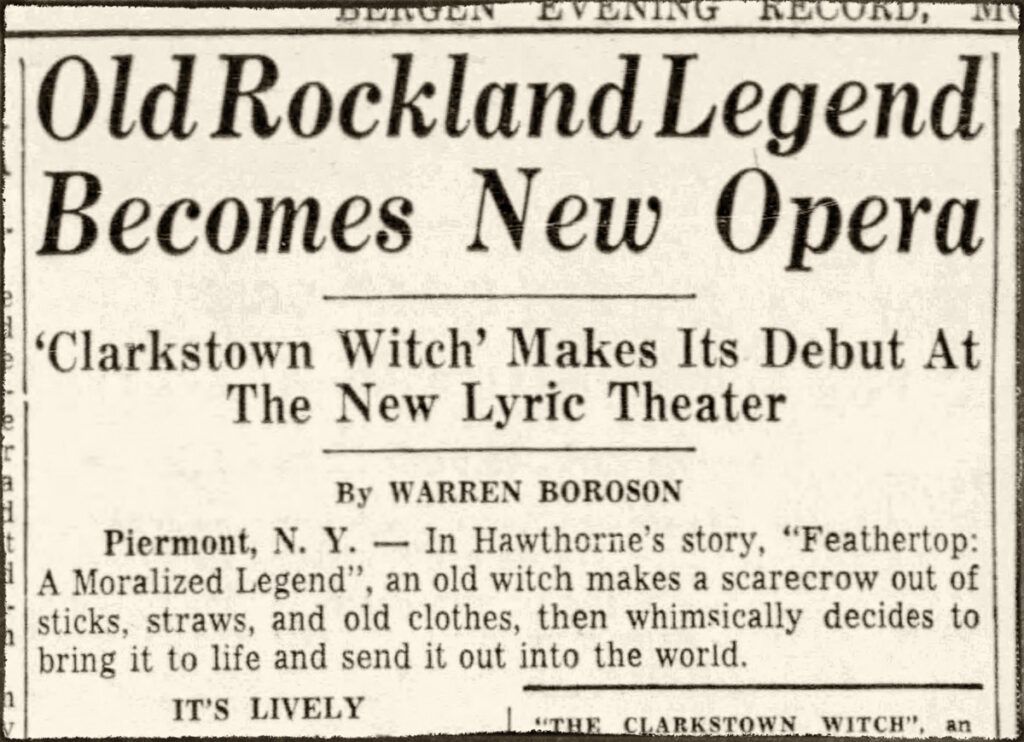

Rockland Conservation Association, with assistance from Hudson River Conservation Society and Spring Valley Historical Society, commissioned a light opera “inspired” by Jane Kanniff and based loosely on the Nathaniel Hawthorne short story “Feathertop” in which a witch brings to life her garden scarecrow. It remains unclear how Rockland Conservation Association determined this production related in any way to the exploration of the Hudson River and Lake Champlain. Unsurprisingly, no critical reviews of the show survive and the script and score seem to have vanished into the mists of time.

The Clarkstown Witch had limited runs at the Rockland Lyric Theater in Piermont, NY during 1959 and 1960.

Clarksville Inn

Built by Thomas Warner around 1840, this building was a stopping place for stage coaches in Rockland County. The historic sign in front of the entrance notes that “It was a center of social life for more than a century and the scene of farewell balls for recruits during the Civil War.” The building went through a major restoration in 1957. Perhaps to bring back a little patina of history, an owner in the 1960s and 1970s seems to have circulated stories that prominent historic figures dined at the establishment and Jane Kanniff, the accused witch of West Nyack, was acquitted in this very building.

While the Clarksville Inn is in close proximity to the De Clark Mill, its construction in 1840 very clearly debunks the claim to the location of a witchcraft trial in 1816. Further, the current owners of the tavern housed in the lower level of the building note on their website “Although legend has it that Martin Van Buren and Washington Irving were once guests, historians now cast doubt on that part of the story.”

Know of another accused witch in the region? No bible-weighing required—just tip the scales in our favor at ghost.editor@sleepyhollowcountry.com.