Hulda the Witch of Sleepy Hollow

“. . . in the days of our nation’s birth-throes he was a brave man who passed the cottage of the witch, even in the daytime. A hundred years ago the people took witches seriously.”

–Chronicles of Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow

Hulda, the witch of Sleepy Hollow, has pulled off quite the magical makeover over the past decade, morphing from a barely-there fictional figure into a full-fledged local legend, complete with her very own headstone at the Old Dutch Church.

Originally, Hulda’s tale was a mere seven-paragraph whisper in Edgar Mayhew Bacon’s 1897 book, Chronicles of Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, nestled comfortably in the “Myths and Legends” section. Bacon suggests that perhaps, long ago, a figure like Hulda may have had some basis in reality. However, his account leans heavily into the realm of legend, leaving little doubt that Hulda the witch, as he presents her, is a myth.

In other words, if you’re going to believe Hulda the witch was real, you’d also have to buy into the rest of the local lore she’s bundled with: a ghostly woman in white crying at Raven Rock, celestial maidens coming down from the sky to dance on Spook Rock, and a phantom Dutch sailing ship cruising the Hudson near Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow. It’s all part of the same spooky package.

Sleepy Hollow Country is filled with historians and folklorists, yet there’s a conspicuous lack of historical references to Hulda specifically, or even to a local witch more broadly. Edgar Mayhew Bacon, who first introduced her story, didn’t provide any sources, raising the reasonable suspicion that he may have simply invented her. Writing 120 years after Hulda’s supposed death, he certainly had no access to first-hand accounts—assuming, of course, there was ever anyone to account for in the first place.

Contents

Hulda the Witch in the 20th Century

And so Hulda the witch remained from 1897 until the mid 20th century when she began to make intermittent appearances in local newspapers. Writing a 1954 series of articles on “Myths and Legends” for the Tarrytown Daily News, Gene Chillemi mostly stuck with Bacon’s original tale. He did, however, give Hulda a skill with languages that has been picked up by most subsequent retellings: “Her knowledge of languages gave her easy converse with Indians.”

In 1975 Hulda made another appearance in Tarrytown Daily News in an article that was part of a series for the national Bicentennial celebration. In “Was Hulda witch or heroine?” Mrs. Jack A. Dorland (Byrl Brown Dorland) presented a major upgrade to Bacon’s sparse tale. Represented by the Daily News as a factual article, Dorland introduced a small cast of supporting characters that would come to characterize later representations of Hulda: Mynheer Requa who discovers Hulda’s hut hidden in the woods, Reverend Ritzema who orders his flock to shun the suspected witch, a Native American translator (speaking no English or Dutch, in this telling Hulda is fluent in at least one native language), and Old Ben, the church sexton who recounts a battle during the American Revolution in which Hulda saves the community from attack by the British:

“Things looked really bad. The redcoats out-numbered us three to one. We were getting the worst of it. About this time, Hulda appeared, carrying her musket. She took a place in the front line. She fought better than a dozen of us. She renewed our courage. On that day, Hulda the Witch turned the tide for us.”

Old Ben, sexton of the Old Dutch Church, Tarrytown Daily News, November 28, 1975

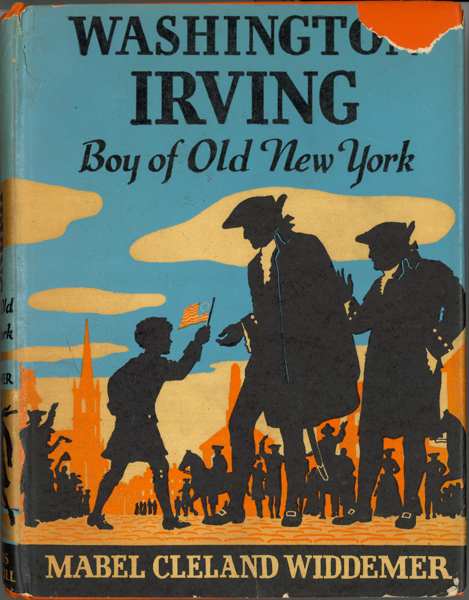

Dorland even boldly asserted that “On his first visit to Tarrytown in 1796, Washington Irving heard the legend of Hulda and visited her grave in the Old Dutch Churchyard.” These additions to Bacon’s original Hulda tale had us puzzled. How and why had he neglected such rich material? Dorland, fortunately, revealed her source: a person she identified as “historian Mabel Cleland Widdemar.” In the age of search engines and online archives, just a few clicks led us to the 1964 New York Times obituary of Widdemar: “GLOVERSVILLE, N. Y., Aug. 5—Mrs. Mabel Cleland Widdemer, author of verse, novels and children’s books, died here today at the age cf 71.”

Widdemer, it turned out, wrote several books for the “Childhood of Famous Americans” series published by The Bobbs-Merrill Company, including fictionalized biographies of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Washington Irving, and James Monroe. Indeed, in her 1946 book of children’s fiction, Washington Irving Boy of Old New York, Widdemer included a chapter titled “Hulda The Witch”.

Widdemer imagines Washington Irving entering the world of his own tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”. New to Tarrytown, a young Irving is befriended by Katrina Van Tassel and her brother Harry. Harry and Washington vow to be friends forever and set out exploring the local landscape and its history. They hunt and fish together, they dig for pirate treasure at Captain Kidd’s Rock. And they explore the burying ground of the Old Dutch Church where they meet Old Ben, the church sexton, who introduces Irving to the tale of an alleged witch: Hulda, an herbalist who conversed with Native Americans, was shunned by her Dutch neighbors, who found redemption by taking up arms to defend her community against an attack by the British.

After this expansion by way of children’s fiction, Hulda the witch slipped back to relative obscurity for another 36 years.

Hulda the Witch Becomes “Mother Hulda”

Then in 2011 a cottage industry sprang forth from Bacon’s short vignette. Her first major step toward becoming a real person came when storyteller Jonathan Kruk published Legends and Lore of Sleepy Hollow and the Hudson Valley. No longer simply Hulda the witch, Kruk wove an origin story for “Mother Hulda”, based “on Dorland, Bacon and other sources.” Putting a sheen of authenticity on his own embellishments, Kruk restated Dorland’s spurious assertion that none other than Washington Irving himself learned of Hulda while visiting the Old Dutch Church in his youth.

Kruk significantly expanded Hulda’s backstory. She is either a widow of a Native American or perhaps a former captive of a local tribe. She has a thriving trade in baskets, furs and herbal medicines, a regular route which stretched from Tarrytown to White Plains. She becomes a renowned healer whose gifts of cures were reciprocated privately with manufactured goods like sewing needles, cookware and lamps. And she picks up a foil in the form of a local clergyman, Reverend Ritzema, who decrees from his pulpit that the suspected witch must be shunned.

While Kruk retains Bacon’s telling of the skirmish between local militia and British Redcoats in which Hulda plays a defining role as a sharpshooter, he adds a chase scene in which she deliberately leads the British away from town. As with Bacon’s original, Hulda sacrificed her life for her neighbors and is buried in the yard of the Dutch Reformed Church in an unmarked grave.

Hulda the Witch, Action Hero

Since 2020 two different entertainment productions have added their own embellishments to Kruk’s fictional backstory. One runs in the woods of Rockefeller State Park Preserve and the other at the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow.

These expanded details of Hulda’s life include a husband, seven years as an indentured servant in a colonial Dutch household, training by an enslaved African woman in the arts of herbal healing, captivity among the Wappinger band of Native Americans, the near-miraculous ability to cure malaria not once but twice (one cure being a Native American sachem’s son), relentless persecution by Domine Johannes Ritzema of the local church, a secret society of trusted friends, swashbuckling chase scenes worthy of Lara Croft Tomb Raider, and a climactic moment when she all but single-handedly rescues the American Revolution from collapse.

A Headstone for Hulda the Witch

In 2019 the congregation of The Reformed Church of the Tarrytowns installed a newly carved monument near the north wall of the Old Dutch Church. It records her curriculum vitae in stone: “Hulda of Bohemia. Died c. 1777. Herbalist, Healer, Patriot. Felled by British while protecting the Militia. Buried here in gratitude for her sacrifice.” And just like that Hulda the witch of Sleepy Hollow became a real, historical figure despite the lack of historical or archaeological evidence for her existence.

Despite her ever expanding résumé of modern exploits, the original Hulda story is poignantly beautiful in its simplicity. After the break is Bacon’s original 1897 tale of Hulda, The Witch.

HULDA, THE WITCH

Reference has been made to the cottage of Hulda, which was not far from the Spook Rock. To-day nothing is left of that humble habitation but a few stones in the side of an alder-covered bank, and the trace of a path leading to a walled spring. But in the days of our nation’s birth-throes he was a brave man who passed the cottage of the witch, even in the daytime. A hundred years ago the people took witches seriously.

Hulda was a Bohemian woman, who came without references or kin and settled in the midst of conservative folks who were familiar with each other’s grandparents. To be a stranger was to be open to suspicion ; to be alone was not respectable. Acting upon a well-known principle, recognized in most rural communities, the newcomer is held to be guilty till he has proved himself to be innocent.

Hulda gathered herbs, “simples,” in the mill woods ; she knew where the boneset grew, and vervain, and mandrake, and calamus. Her cabin was full of the sweet odor of plants a-drying ; specifics for colds and fevers and the unsophisticated pains and aches of simple folk. She wove baskets, too, and was wise, as a woman ought not to be. Rumor, as busy in Sleepy Hollow in 1770 as she is in 1897, said that the witch had commerce with the Indians who came occasionally into this region from far up the State, and exchanged with them secrets of black art and “yarbs.”

A tapu, as effectual as ever existed in the South Sea islands, cut this woman off from human intercourse, and when the war came she, alone, had no friend to discuss her hopes or tell her fears to. From first to last the neutral ground got the worst of the Revolution. Friends and foes struggled across it and fought or fled back again. Every crime in the calendar was committed in the names of King and Congress alike, till the harried remnant of the people sat among their denuded fields and depleted barns, and faced starvation and sickness with such stoicism as they could muster. Sometimes an undetected hand left dainties that were hard to procure, on the door-step or the window-sill of some house where want and pain had settled together ; but the donor was invisible.

In those days men patrolled the highways to intercept the cattle-thieves that ran off their stock, and as the population became smaller, the women sometimes took their places with flint-lock and powder-horn. Hulda, the witch, presented herself for this service, but no one wanted her companionship. At last one day a force of British landed from one of the transports that had sailed up the Hudson and commenced a march which was to bring them, by means of the King’s highway, to the rear of Putnam’s position, at Peekskill. As they marched in imposing array a volley greeted them from behind walls and tree-trunks. It was Lexington repeated in Westchester County. Not to be repulsed this time, Hulda fought with her neighbors, using her rifle with great effect, so that she was singled out for vengeance ; and before the redcoats retreated to their boats they had, by means of a sortie, overtaken and killed the witch.

Animated by a new respect, those who had seen her fight avowed that, witch or no witch, she had earned a right to Christian burial. Reverently they carried her to her cabin, and while there discovered between the leaves of her Bible (?) a paper informing them of a little store of gold that she desired to have distributed among the widows whose husbands had fallen for their country.

Hulda’s grave, it is said, is close by the north wall of the old church, as though her neighbors, having done her what despite they could during her lifetime, were desirous to atone after her death by an exhibition of hearty respect.

Know of a witch whose legend deserves a headstone of its own? We’re always gathering herbs for our collection. Email us at ghost.editor@sleepyhollowcountry.com.