The Legendary Headless Horseman Bridge

“The bridge became more than ever an object of superstitious awe, and that may be the reason why the road has been altered of late years, so as to approach the church by the border of the mill-pond.”

-“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, Washington Irving

More than 200 years after publication of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow“, the headless horseman bridge is one of the most popular destinations in Sleepy Hollow. Every October it is sought out by thousands of visitors from around the globe. Unfortunately, the original bridge where Ichabod Crane lost his race with the Headless Horseman no longer exists.

The simple wooden span that crossed the Pocantico River in the late 1700’s has long since rotted away. In fact, Sleepy Hollow village historian Henry John Steiner has documented at least five distinct bridges that carried the Albany Post Road over the stream. No trace remains of any except the most recent, the 4-lane concrete and steel U.S. Route 9 (the modern successor to the colonial-era Albany Post Road) bridge constructed by William Rockefeller in 1912. Even that was heavily modified in the 1930s when New York State reconfigured the route of the road.

But don’t despair! We took a deep dive into the archives to bring you this history of Sleepy Hollow’s Headless Horseman Bridge including several spots you can visit today. Much of the history of this bridge remains murky, at best, and in several cases significant discrepancies are reason to be cautious about making definitive claims.

Contents

Original Location of the Headless Horseman Bridge

In “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, published in 1820, Washington Irving observes “the road has been altered of late years, so as to approach the church by the border of the mill-pond.” The map below from the Sleepy Hollow and Tarrytown Historical Society dates to 1725 with revisions as late as 1795. Since “The Legend” is set in the years immediately after the American Revolution, this is likely the position of the bridge Irving had in his mind.

This is not a surveyed map, so it is not possible to say for sure how this overlaps with modern roads. However, it seems possible the Albany Post Road followed what today is Holland Avenue and crossed the Pocantico River inside what is now Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. From there, the road turned south on what is now the cemetery driveway before snaking around the church and up the hill. There are no surviving traces of this bridge or its abutments.

The King Post Sleepy Hollow Bridge

This is purported by some to be the version of the Sleepy Hollow bridge Washington Irving had in mind when writing “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”. However, it is the most problematic version. The biggest issue is that the earliest known sketch of the bridge shows the road approaching the church by the border of the millpond. This does not agree with either the location Irving described or with the map above from the era in which “The Legend” was set.

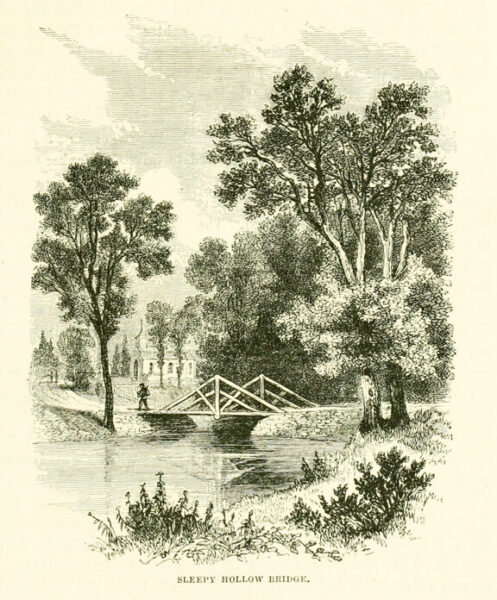

American historian Benson John Lossing is best known for his illustrated books on the American Revolution and Civil War. In his 1866 volume The Hudson, From The Wilderness to the Sea, Lossing included this woodcut illustration of the Sleepy Hollow bridge. In his preface, Lossing indicates he made preliminary sketches of all woodcuts from 1860 to 1861.

If Lossing sketched this bridge in person, it is possible Irving would have been familiar with it since he died only a year before Lossing allegedly paid his visit.

Lossing’s sketch is one of the earliest known and most detailed images of the headless horseman bridge and the one which establishes its king post design with parallel diagonal braces. The single king post (alternately, king pole) is one of the oldest and elementary truss designs used in timber bridge construction. It consists of a horizontal beam (the bottom chord), a vertical beam (the king post), and diagonal braces to distribute load to the bridge abutments. The Federal Highway Administration notes that this design was used primarily for relatively short spans of twenty to thirty feet with few historic examples remaining in the United States.

The king post bridge became the standard souvenir post card of the bridge into the early 1900s with versions issued by most of the local souvenir vendors. Versions of it are still in use today at several gift shops around Sleepy Hollow.

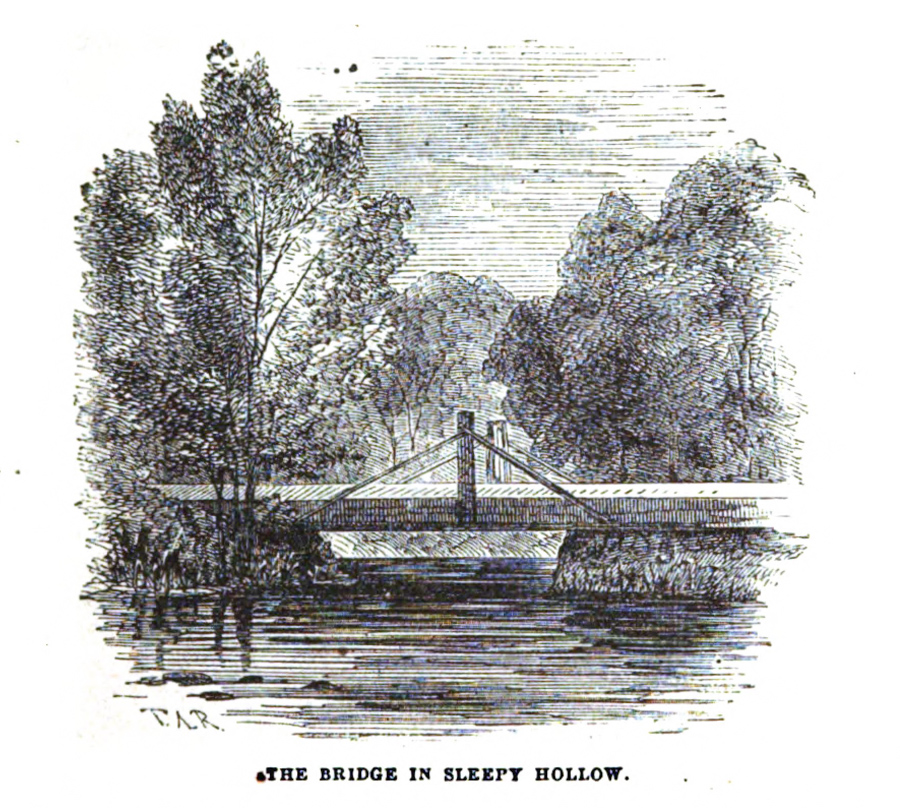

Published in the same year as and competing with Lossing’s book, Miller’s New Guide to the Hudson River with illustrations by T. Addison Richards produced this alternate version of the king post Sleepy Hollow bridge. It deviates in appearance with a single set of diagonal braces rather the parallel sets seen in Lossing and Farrington.

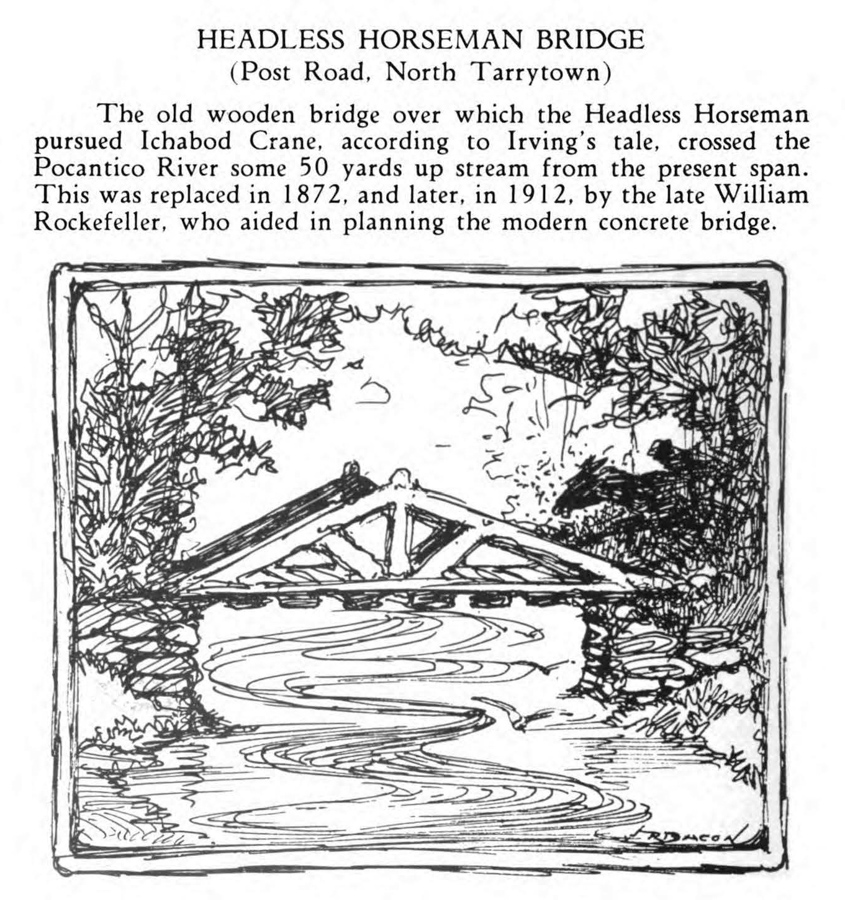

In 1939 the Tarrytown Historical Society published a visitors guide titled Historical Tarrytown and North Tarrytown (a guide). In it they reproduced a version of the headless horseman bridge closer in style to Miller while indicating it stood as late as 1872.

If, as the historical society claimed, this small Sleepy Hollow bridge still stood in 1872, it must have been abandoned and unused in favor of a newer bridge on an amended route of the Albany Post Road. There is no possible way it would have supported the wagon and carriage traffic of the day. By 1872 Tarrytown and North Tarrytown were home to factories of the Pocantico Tool Works, Rand Drill Co., Brounbacker’s Silk Factory and others. Stone quarries abounded in the surrounding hills. There were waterfront lumber, coal and brick yards transporting material to the grand estates of Kingslands, Rockefellers, Phelpses, Archbolds, Lewises, and Aspinwalls. This bridge wouldn’t have survived even the somewhat lesser traffic of the 1850s.

The most glaring issue with identifying this bridge as the actual bridge in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is that the first surviving images of it appear nearly 50 years after publication of the short story. It is exceedingly unlikely this rudimentary design of limited load-bearing capacity, strung low to a river that notoriously floods every couple years, had a longevity measured in decades. It likely was rebuilt every couple years.

For the last word on the king post headless horseman bridge we turn to the coverage of Irving’s funeral in the New York Times on December 2, 1859. By the time of Irving’s death there was very clearly a new bridge in place of the old:

“Sleepy Hollow is within a stone’s cast, and the spot where the old bridge was, and now is not, where the spectral trooper decapitated himself lies, not very many rods away. The new bridge yesterday was over-arched with mourning draper and branches of yew.”

New York Times, New York, NY. December 2, 1859.

Kingsland’s Stone Arch 1850?-1912

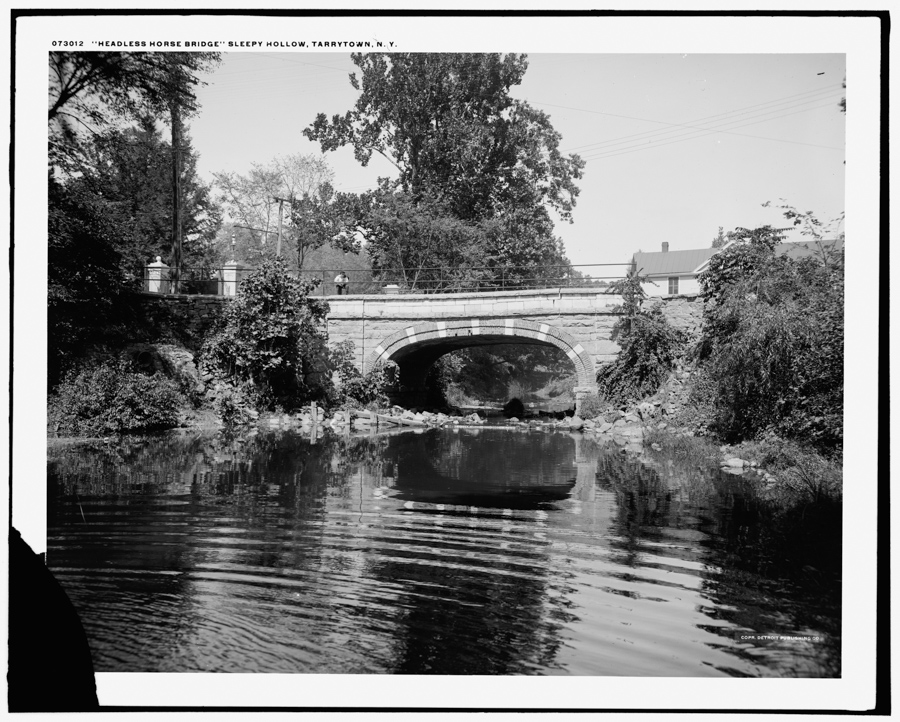

The stone arch Sleepy Hollow bridge in the photo below would have been better capable of handling the heavier road traffic of the second half of the 1800s. Clues about its date of origin cropped up in newspaper articles after its demise. The New-York Tribune wrote on June 7, 1912, “The bridge was built by Ambrose Kingsland when he was Mayor of New York City.” In an unattributed article on January 27, 1940, The Daily News, Tarrytown, NY, corroborated the Kingsland connection: “The old bridge was built by Ambrose Kingsland, owner of Kingsland Point, about 1856.”

Whether built when Kingsland was mayor from 1851–1853 or as late as 1856, the date of this bridge seems a little more certain than the king post version. It sounds plausible Kingsland was involved. He had the money and expertise to get a relatively small bridge built, and it would have greatly improved land access to his estate. Kingsland was a wealthy whale oil merchant and two term mayor of New York City who had a country home at Tarrytown. He was at one time a commissioner of the city’s Croton Aqueduct and later pitched the idea for Central Park.

This structure was higher off the stream to better withstand floods (more about that later) and wider to accommodate increased road traffic. The significant shifting of stones on the right side of the bridge is a sign of settling and instability, which was a contributing factor in William Rockefeller replacing this headless horseman bridge in 1911.

On the left of the bridge is the South Gate of Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, significantly closer to the Albany Post Road than it is today. The road moved, the gate did not. On the right is the roof of S. J. Sackett & Co., a cemetery monument dealer, a business later taken over by William Smith Memorials. The monument company building was demolished in the early 2020s.

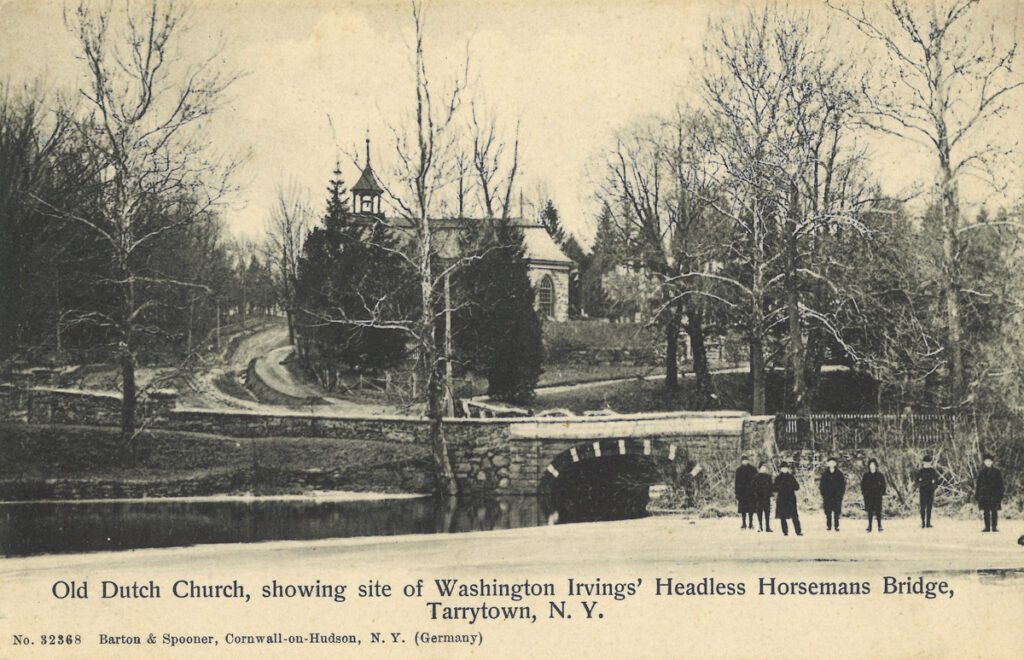

At this point in time the Albany Post Road, which the Sleepy Hollow bridge carried across the Pocantico River, had a slightly different route than it does today. In the postcard below you can see the roadbed took a hard turn to the east just below the Old Dutch Church, rather than continuing straight as it does today.

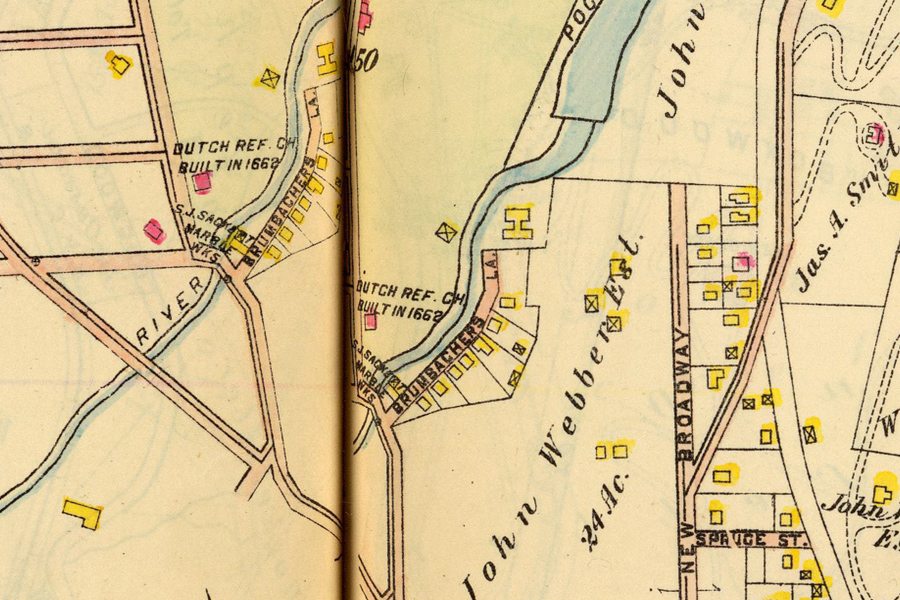

Maps of the era show the Albany Post Road making an almost 45 degree turn below the Old Dutch Church to cross the Sleepy Hollow bridge. The facing page maps below are from Atlas of Westchester County, N.Y. Pocket, Desk and Automobile Edition produced by G. W. Bromley & Co. in 1914. Although date of publication is after the construction of the next generation Rockefeller bridge, the map appears to show the position of the stone arch bridge.

To place this in modern context, Brumbachers Lane mostly overlays today’s Dell Street. The “I” shaped building at the end of the lane is the Brumbacher tool factory which was powered by a dam on the Pocantico inside what today is Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. Remnants of the factory’s dam are still visible inside the cemetery. The Bellwood Avenue crossing of the Pocantico, the street to the left of the letter “R” in river, was likely never built. Bellwood was instead routed out Pierson Avenue to the intersection at the Old Dutch Church.

While this stone arch was no doubt more durable than the old wooden bridge, it had a close call in October of 1903. A massive rainstorm lashed the area with nearly 10 inches of rain in 24 hours, causing widespread devastation and flooding. The Sleepy Hollow bridge didn’t escape unscathed, with The Yonkers Statesman reporting that a portion of its abutment collapsed.

“Under the onslaught of the flood, the Pocantico Bridge, at Sleepy Hollow, began to fall. Eight feet of the wall on the north tumbled over. This bridge is famous the world over, and is known as the ‘headless horseman’ bridge . . . The Pocantico rushes under it, and so great was the torrent that its walls were weakened.”

The Yonkers Statesman, Yonkers, NY. October 10, 1903.

All sources seem to agree that the end of this bridge came on June 6, 1912. The New-York Tribune wrote on June 7, “The famous old Pocantico bridge, known the world over as the “Headless Horseman’s Bridge,” went down last night with a crash. Workmen were busy several days with wedges undermining it, and it fell at exactly 5 o’clock.”

On June 6, 1937, the 25th anniversary of the destruction of the Kingsland bridge, The Daily News, Tarrytown, NY, embellished its demise with a little local legend: “The Old Pocantico Bridge, known throughout the world for the postcard representations as the scene of Ichabod Crane’s downfall, fell down itself on the afternoon of June 6, 1912, just as the whistle sounded the knell of the working day at the Maxwell-Briscoe plant across the marsh. Workmen had been undermining it for several days.”

Rockefeller Bridge 1912-1934

This is the spot which New York State marked with a blue and yellow historic marker as the location of the original headless horseman bridge. However, in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, Irving describes the route of the Albany post road on the east side of the Old Dutch Church (now it runs on the west side), putting the original headless horseman bridge inside what is today Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

William Rockefeller, younger brother of John D. Rockefeller, owned a Gilded Age mansion on the Albany Post Road just north of Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. In 1911 he offered a generous donation to the village of North Tarrytown toward paving roads downtown if the village would also agree to replace the dilapidated and dangerous Sleepy Hollow bridge across the Pocantico River. He donated generously toward the bridge as well, with the condition it be dedicated to the memory of Washington Irving. Work commenced on the new span in 1912.

In its October 1911 issue, The Westchester County Magazine wrote of the proposed new bridge, “It will be built of faced stone, 92 feet long and 50 feet wide, and will be much larger and handsomer than the old bridge. The latter is narrow and on a curve, and is considered a dangerous place for automobiles traveling on the Old Post road. The new bridge will be straight and the curve in the road will be eliminated.”

Rockefeller appeared resolute to make his new headless horseman bridge a memorial to Washington Irving, not himself. On August 8, 1912 The New York Press reported that when village officials installed a bronze tablet on the bridge naming him as the benefactor, Rockefeller had it removed. Less than a week later, however, he changed his mind. The Columbia Republican of Hudson, NY reported on August 13, 1912, “When he first heard about heard about the inscription, he ordered it taken off, but gave no reason. There was much surprise at his action, and there was equal surprise when he decided to accept the honor.”

Not everyone was impressed by the fancy new span. On August 22, 1913, a year after its opening, The Review of Bronxville, NY grumbled about Rockefeller and his bridge: “If in reading Irving’s story your fancy may have heard the clatter of hoofs over an old-style wooden crossway, an illusion may be spoiled when you see the present Headless Horseman’s Bridge. The wealth that summers itself beyond Sleepy Hollow believes in a up-to-date approach to its domain . . . Nothing survives of the span that Irving immortalized.” In its petty complaint the newspaper failed to recognize that any wooden version of the headless horseman bridge had been gone more than 60 years.

1930s Expansion 1934-present

In the early 1930s New York State straightened the roadway to eliminate two sharp curves which had contributed to numerous accidents as well as slowing the pace of traffic over the Sleepy Hollow bridge. In an interesting coincidence, Westchester County engineer Charles MacDonald was assigned the task. This would be MacDonald’s second time rebuilding the bridge for it was he, as a private engineer, who had designed the 1911 span for William Rockefeller.

By all appearances, MacDonald preserved the stone veneer and balustrades of the Rockefeller bridge while widening the roadbed from 28 feet to 75 feet. This is the Sleepy Hollow bridge we have today.

We know work on the bridge was underway early in the year 1934 for The Larchmont Times, Larchmont, NY, issued this traffic advisory to Westchester County motorists on April 12: “In North Tarrytown the Headless Horseman Bridge is being extended to accommodate the re-paved road, which is being re-located for a short distance to eliminate the sharp curves which have made this section of the Post Road particularly dangerous when traffic is heavy.”

While straightening of the Albany Post Road (now called Broadway) certainly speeds traffic across the Pocantico River, it has resulted in the confusing convergence of Pierson Avenue, Gordon Avenue, Dell Street, Old Broadway and the South Gate of Sleepy Hollow Cemetery with 2 northbound and 2 southbound lanes of Broadway. It is such a broad expanse that visitors are sometime surprised it is a bridge at all.

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Bridge

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery’s modern bridge is seen frequently in social media feeds. It is not, however, in the original location of the Sleepy Hollow bridge. Rather, it is far upstream from where the Albany Post Road bridge stood in Washington Irving’s time.

The present version of the cemetery bridge was constructed in the 1990s. It is dressed in rustic fashion and very popular for selfies. Find it on cemetery road “Sleepy Hollow Avenue” about 0.3 mile inside the cemetery’s south gate. Be respectful when visiting. The cemetery is private property, access is not guaranteed to anyone but lot owners. Do not block the bridge or the approaching roads. The cemetery bridge is used daily by funerals and mourners visiting graves. Find information on visiting Sleepy Hollow Cemetery here.

This bridge connects the main portion of the cemetery on the west bank of the Pocantico River with 10 acres on the east side. When the cemetery purchased those woodland acres from Samuel Rice in 1890, there were plans to cross the river with several bridges. Apparently only one was ever constructed.

“It is purposed to improve this property, connecting it with the west side with rustic bridges, thus adding to the picturesque beauty of the whole.”

Rockland County Journal, Nyack, NY. March 1, 1890.

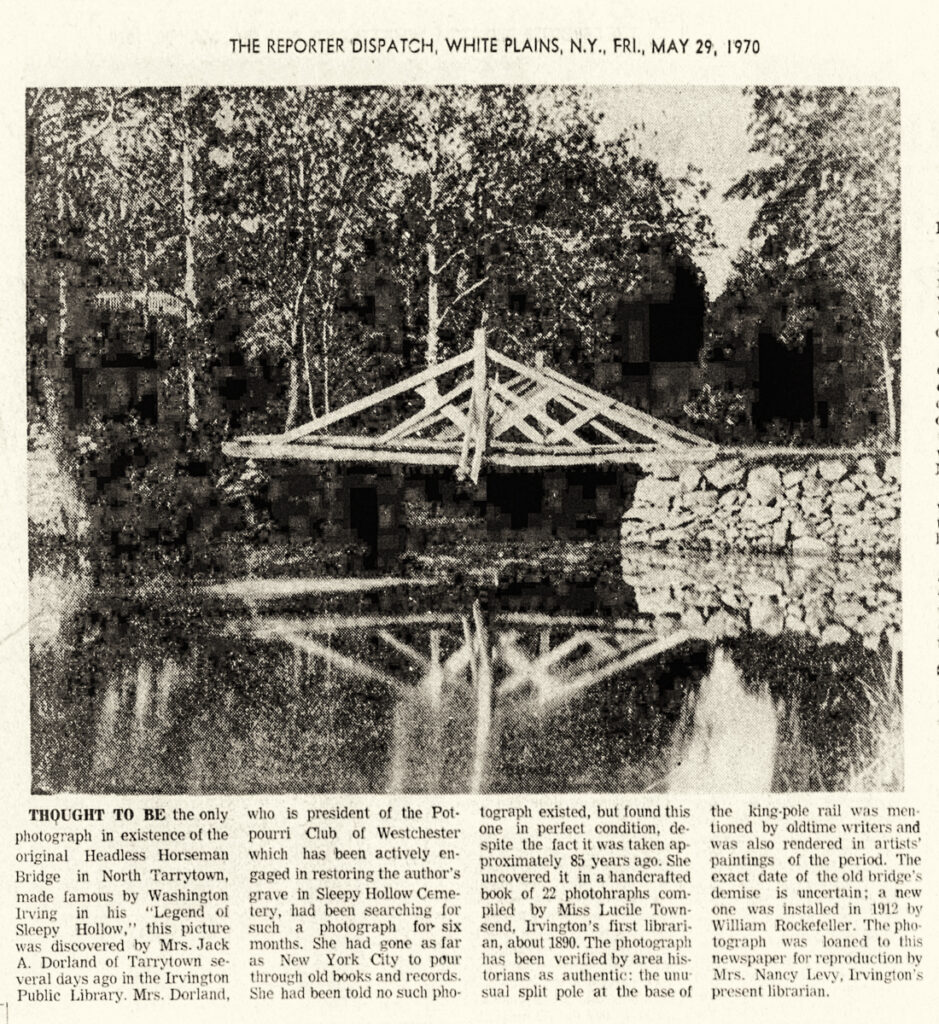

Photo of Headless Horseman Bridge Discovered

In 1970 The Reporter Dispatch of White Plains, New York reported that Mrs. Jack A. Dorland of Tarrytown discovered what was “thought to be the only photo in existence of the original Headless Horseman Bridge in North Tarrytown.”

Today, in an era where nearly everything can be found with a few clicks of a mouse, it’s easy to overlook the true difficulty of her accomplishment. Back then, before the advent of search engines and digital databases, finding a single photograph could be an exhausting and time-consuming task. Mrs. Dorland had spent months combing through archives in New York City and Westchester, visiting libraries, dusty file cabinets, and old collections. Her persistence finally paid off when she discovered the elusive image at the Irvington Public Library, tucked away in a handcrafted book of 22 photographs, compiled around 1890 by Lucile Townsend, Irvington’s first librarian.

The photograph, preserved as a half-tone image in the newspaper, closely resembles the Edward Farrington photogravure postcard shown above. While slight differences in printing techniques may account for minor variations, it is highly likely they depict the same scene, tying Mrs. Dorland’s discovery to a larger historical context.

As an aside, Mrs. Jack A. Dorland (Byrl Brown Dorland) also features in our article on Hulda the witch of Sleepy Hollow.

The Sleepy Hollow Covered Bridge

The Sleepy Hollow bridge has influenced popular culture for more than two centuries. Walt Disney and Tim Burton dressed up their visions of Sleepy Hollow with covered bridges to great effect. There is no evidence, however, in Irving’s story or historical records that the real Sleepy Hollow bridge ever had a roof. Covered bridges were used further up the Hudson Valley, almost always to span rivers broader and deeper than our little creek.