The Last Tarrytown Castle

Carrollcliffe, standing at one of the highest points in the village, is the last surviving Tarrytown castle. There were once two castles here. Or maybe four depending on who you ask and how you choose to define a castle. Just north was Ericstan, a castellated villa by Alexander Jackson Davis that was demolished in 1944. To the west was Edgemont, the painted brick home of Julian Detmer, with decorative crenelations in the style of a castle. To the south is Lyndhurst, which is occasionally described as a castle although it is more accurately a Gothic Revival mansion.

Carrollcliffe was constructed by Howard Carroll, Inspector General of New York state’s troops in the Spanish-American War. His father, also Howard Carroll, was a brigadier general in the Union army during the American Civil War, killed at Antietam. The senior Howard Carroll was a pioneer in construction of suspension bridges.

Contents

The Axe Castle Years

In 1941 Emerson Wirt Axe and Ruth Houghton Axe bought the 45-room Tarrytown castle and 64 acres of land for $45,000. They used it as a home for themselves and their mutual-fund and financial advisory business.

Emerson Axe was something of a Renaissance man. His 1964 obituary in The New York Times noted “In addition to being an expert marksman and authority on fencing and jiu-jitsu, he was a chess expert.” He was reputed, in 1940 at the Harvard Club, to have played six simultaneous chess matches—while blindfolded. Almost incredulously, The New York Times continued “He wound up with a score of three victories, three draws and no defeats. He had a total of eleven opponents with five consultants at five of the boards.”

During World War I Emerson served with the American Expeditionary Forces in France. He later became an economic statistician for the American Telephone & Telegraph Company before starting his own investment firm. Not only an authority on finance, he was an expert on wine. The Tarrytown castle’s climate controlled wine cellar held his private collection of more than 5,000 bottles. In addition to his own firm, he was chairman of the board of Smith & Wesson.

After Emerson’s death in 1964 Ruth assumed leadership of investment advisory firm and the four mutual funds it managed. Adjusted for inflation, the $500 million dollar enterprise would be about $5 billion today. Four mutual funds doesn’t sound like from the vantage point of today, when there are more than 7,000 in the United States alone. In 1964 there were only 300.

Apart from cofounding a successful investment firm, Ruth served on the boards of City Investing Company, Flying Tiger Lines, Smith & Wesson, and Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad. Her energy and velocity were remarkable. One of her staff, who had assumed Ruth was working elsewhere in the castle, once received a card from her, postmarked London, where she had sped off on a sudden business trip. Ruth died in 1967, just 3 years after Emerson. Both are entombed at Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum in Hartsdale, NY.

As the financial industry changed, so did use of the castle. The Great Hall, with its beautiful rose window, became home to the research department. The formal ballroom below became home to the Axe computer department. The 18th-century Oak Room, however, remained unchanged. Brought intact from a former Paris mansion, it was retained as a meeting room.

In 1985 Axe-Houghton Associates was purchased from the couple’s estate by USF&G, snapped up as the insurance company formerly known as United States Fidelity and Guaranty Company rapidly diversified its business. That expansion proved unwise. Reeling from financial difficulties at various operating units, USF&G sold off its mutual fund business and put the Tarrytown castle up for sale in 1990, asking $4 million.

Becoming the Castle at Tarrytown

In 1994 Hanspeter Walder, a private banker and officer of the New York Branch of UBS AG, purchased the castle for about $2 million with the intention to turn it into a high end hotel and restaurant. But first he would need to get the property rezoned from office use only. That would turn out to be the least strenuous part of the project: decades of use as office space needed to be reversed, the proposed high-end restaurant required a modern commercial kitchen, guest rooms were in short supply.

Over the next 7 years Hanspeter and his wife Steffi poured huge amounts of time, energy and money into the project. According to an article in Westchester magazine, the Walder’s brought in woodworkers and stained-glass artisans from Europe, furnished the castle with tapestries and antiques, and stocked up the wine cellar in a way Emerson Axe would have envied. They added stairways and elevators to bring the building up to code, carved an underground passageway through solid rock, and added a guest wing with 24 rooms.

The results were stellar. The Castle at Tarrytown quickly became the place in the county for gala celebrations and weddings. It garnered preservation and architectural awards and was named by Condé Nast to its top 20 best small hotels in America.

All this, however, consumed vast amounts of money, which the architectural and construction teams came to suspect could never be covered by revenues from a boutique hotel and restaurant. They would turn out to be correct but for reasons they never suspected.

On the evening of September 24, 2001 Hanspeter and Steffi Walder celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary with family and friends in the Great Hall of their splendidly restored castle. As Hanspeter raised a glass to toast the occasion, six uninvited guests arrived at the hotel lobby: four FBI agents and two Tarrytown police officers.

Within minutes he was arrested and whisked off to arraignment for draining more than $70 million from very wealthy clients. The purchase and renovation of the castle, as well as an extravagent lifestyle, were the product of a complex embezzlement scheme.

According to a September 2005 press release from the Federal Reserve, Walder ultimately pleaded guilty to 16 counts of “embezzlement and misapplication by a bank officer or employee”. He was sentenced to 97 months in prison and ordered to make restitution of $70 million and pay a fine of $1 million.

The Castle Hotel & Spa

The Walders poured far more money into the castle than it was worth. In 2003 the property sold for $10.9 million to an operator of luxury hotels. It reopened as Castle on the Hudson. In a curious coincidence, a second financial scandal would almost immediately wash over the property. A business manager of the castle was alleged to have stolen more than $400,000 from its accounts between December 2004 and October 2008.

The hotel and Equus restaurant remained popular. With the addition of Sankara Spa on premises, the property rebranded as The Castle Hotel & Spa. While both restaurant and spa were highly regarded, neither survived the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023 the hotel restaurant reopened as Emerson & Ruth while the spa operates as The Spa at the Castle, both seasonally. Weddings and corporate events operate year round, mixed with special events like 2023’s Headless Horseman Ball.

The Final Carroll Residence

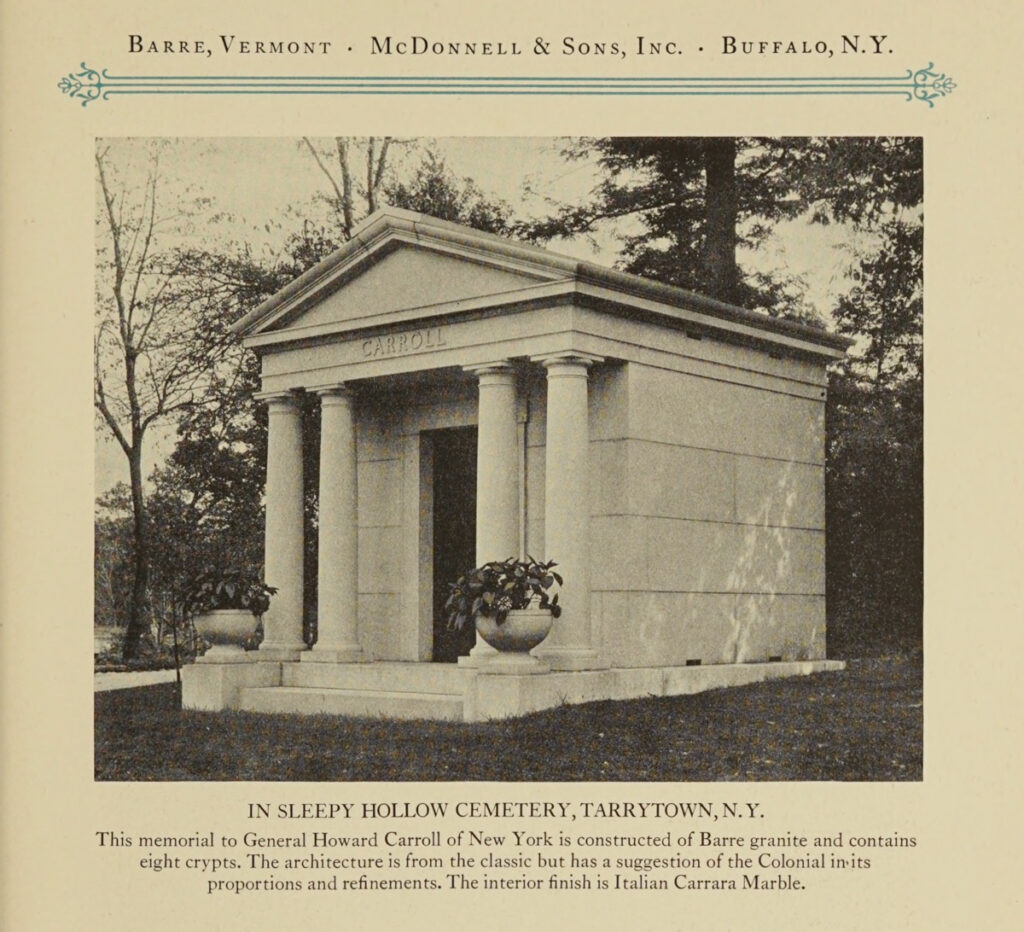

After Howard Carroll’s death his wife Caroline purchased a lot in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery and hired McDonnell & Sons, Inc. of Buffalo, New York to construct a mausoleum.

Established in 1857, McDonnell & Sons had executive offices in Buffalo with quarries and a finishing plant in Barre, VT. The excerpt below from a 1922 McDonnell monograph states that the exterior is of Barre granite with interior of Italian Carrara marble and contains 8 crypts. Cemetery records show there are an additional 4 crypts under the floor, bringing total crypts to 12.

The mausoleum sits at one of the highest points in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, facing the Hudson River.