Speed, Glory, and Tragedy: Sleepy Hollow’s Lost Bobsled Champions

While the origins of bobsledding are often contested between the Swiss Alps and upstate New York’s Adirondack mountains, compelling evidence points to the Hudson Valley as the sport’s birthplace. In Albany’s bustling lumber district along the Hudson River, rough-hewn lumberjacks transformed working sleds into racing machines during the 1880s. Newspaper reports confirm Albany held organized bobsled races at its winter carnival as early as 1885, predating Swiss competitions by two years. An 1882 exam for Albany eighth-graders even asked students to write about bobsledding, suggesting the sport was already part of local culture.

The sport’s innovation was elegantly simple: some daredevil, understanding that more weight equaled more speed, linked two short coasting sleds together with a plank creating a vehicle that could carry enormous loads—and achieve terrifying speeds. The front runners were hinged and controlled by rope, allowing for steering as the sled hurtled downhill.

What began as utilitarian equipment in lumber yards quickly evolved into custom-built racing machines as the craze spread through the Hudson Valley. From Albany, bobsledding fever swept south to communities like Tarrytown and North Tarrytown (now Sleepy Hollow), east into Connecticut, and north through the Mohawk River Valley to the Adirondacks. Here in Sleepy Hollow Country, master craftsmen would perfect the art of sled building, transforming this rough-and-tumble lumberjack pastime into a winter spectacle that captivated the entire region.

Contents

Leander Jacobs, Master Sled Builder of Sleepy Hollow Country

Tarrytown and North Tarrytown were home to several top-notch sled builders whose craftsmanship dominated races in the Hudson Valley from here to the Catskills and east into Connecticut. Among them were Henry Godstrey, Otto Boock, and the Denton family. The greatest of these builders was Leander Jacobs.

Born in Brewster, New York, Jacobs lived for decades in a house at the northwest corner of College Avenue and Valley Street. La Esquina Latina market occupies the lot today. He was by trade a landscape gardener, working on the large estates in the area and also for Frank R. Pierson who operated large scale greenhouses and plant nurseries.

“It’s a real he-men’s job to handle a big bob loaded down with eight or 10 men and making a speed of a mile a minute. But Leander in his day held it down with the best of them. Hence the famous old war cry of ‘Hold her down Leander’. And by the way, Leander doesn’t look any older than he did 20 years ago when he was ‘holding her down.'”

Tarrytown Daily News, 13 December 1926

Jacobs turned out a number of competition sleds in the early 1900s, among them the “Vamoose” and the “Standard”. He sold the former to John Wilkins and a friend, who in a single winter season collected $500 in prize money (more than $15,000 today) from races around Westchester County. As fast as the Vamoose was, Jacobs was confident his own sled, the Standard, was even faster.

The Boock Brothers

Leander Jacobs’s chief rivals on a sled were brothers Fred and Otto Boock. Fred, a great sportsman, owned several businesses on Tarrytown’s waterfront: the Washington, a supply shop at the Nyack-Tarrytown ferry dock, and a beer bottling plant. His spare time was often spent on the Hudson River. Fred’s sailboats placed first in many Hudson River regattas. When the river froze over, Fred was a speed king on ice skates and in his ice-boats.

The Last Bobsled

The decline of street racing bobsleds coincided with the rise of the automobile. As the sport disappeared from local streets in the late 1920s, so too did the sleds vanish into the mists of time. In November 1968 Tarrytown Daily News noted that Fred Boock’s famous winning sled “999” was consigned to the basement of a home on Hunter Avenue in North Tarrytown (now Sleepy Hollow). We’ve turned up no trace of the sled since then, nor have we tracked down any of the other winning sleds from Sleepy Hollow’s golden age of bobsledding.

It still exists! We are referring to that champion of champions — the bobsled wonder — “The 999” — which was owned by the late FRED BOOCK, and won its share of trophies and high stakes from Long Island to Connecticut. EDDIE BECK SR. has the old bobsled in the basement of his home at 115 Hunter Ave. We would like to see it taken from the moth balls and repolished to its original splendor and we are willing to wager that it could still put to shame many of those bob-sleds found in the Adirondacks and in Maine.

The Daily News, Tarrytown, NY, November 25, 1968

However, there is still one sled in town. Tarrytown Patrolman Charlie Schneider, who lived in the south end of the village, had a sled he would run on Paulding Avenue and other hills in the Pennybridge section of Tarrytown. His “Laura T.” still hangs where it did at the time of his death in September 1958.

Injuries and Fatalities

Flying down a slick hill at 60 miles per hour was not only exhilarating, it was inherently dangerous. All the more so since racing in the Hudson Valley was most often conducted on public streets where vehicles, livestock, and pedestrians were constant obstacles. There was always the chance of a catastrophic crash involving serious injury and even death. Two accidents twenty years apart illustrate the risk.

Rain and hail on Thursday, December 11, 1902 froze overnight making hills icy and dangerous. Naturally, the hills all over Westchester County were crowded with sleds on Friday. Eight boys launched the sled “Defender” on the steep incline of Wildey Street in Tarrytown. On account of ice, William O’Keefe, the steerer, lost control of the bob at Storm Street where it crashed into a pile of lumber at the curb. Boys flew in all directions. 14-year-old William Baldicini’s arm broke in three places while John Herguth suffered internal injuries. John O’Keefe, William’s cousin, suffered a fractured skull and was taken to the nearby Tarrytown Hospital along with Baldicini. John never regained consciousness and died a few days later of his injuries. Police temporarily suspended sledding on the hill.

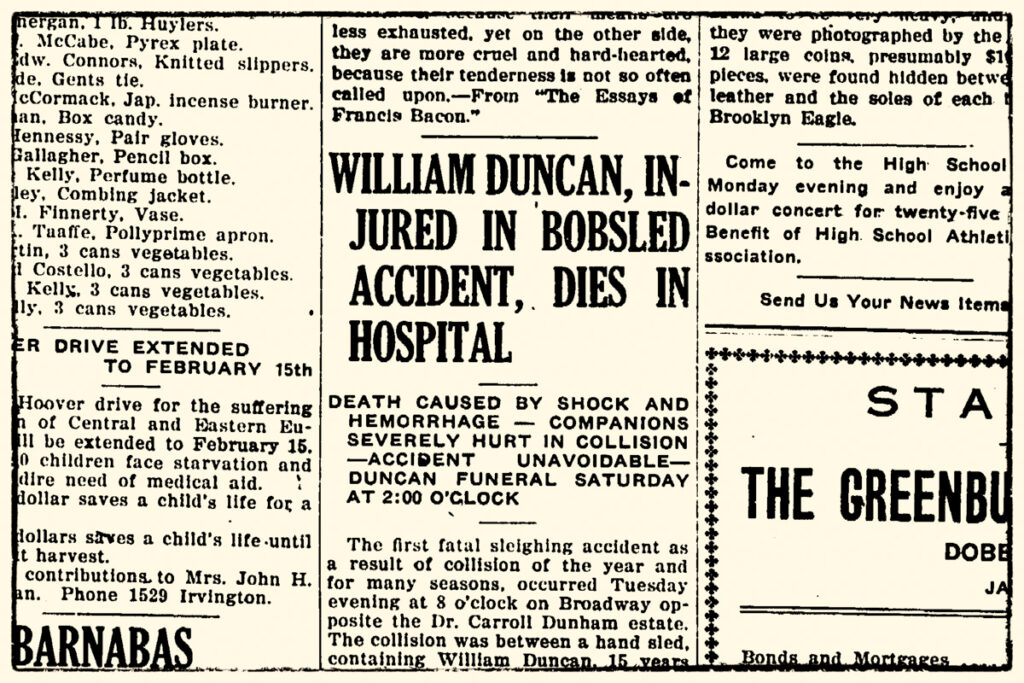

Two decades later casualties were still piling up. On Tuesday, February 1, 1921 around 8 pm, William Duncan and Fred Bliss were riding a “hand sled” on Broadway just south of Main Street in Irvington. Coming the other direction was what the Irvington Gazette described as “a large super-bob owned by David Murphy, Jr., and loaded with a party of young people.” When the larger, faster sled swerved to avoid an automobile, it collided with the smaller sled. Duncan received fatal internal injuries and Bliss was knocked unconscious. The bobsled party was thrown off, with several suffering severe injuries. Duncan was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery not far from John O’Keefe.

Sleepy Hollow’s Bobsled Legacy

Today, the echoes of “Hold her down Leander!” have long since faded from Tarrytown’s icy slopes, and the last bobsleds have been consigned to dusty barns and forgotten basements. Yet there remains one place where the men who built these speed machines and those who perished riding them share a strange kinship: Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. The granite headstone of master craftsman Leander Jacobs overlooks the Pocantico River not far from where young John O’Keefe lies, victim of a December day when ice claimed steering and sleds alike. The Boock brothers’ family plot rests behind the chapel, a silent monument to the artisans who transformed planks and runners into instruments of glory—and occasionally tragedy. In death, as in life, the golden age of bobsledding remains part of Sleepy Hollow’s landscape, where thrill-seekers and master builders have come to rest in the same haunted earth that once trembled beneath their sleds.