The Bard of Tarrytown

The Bard of Tarrytown. The Poet of the Pines. The Tanyard Poet. The World’s Most Gifted Seer, Palmist and Medium. These were just some of the professional titles used by the tireless and shameless self-promoter John Henry Titus throughout his long life. He missed the chance to apply even more apt titles to himself: Spinner of Yarns, Teller of Tall Tales, Purveyor of Pablum. Hold on as we explore the life of John Henry Titus through a trail of newspaper advertisements, news articles, and self published books.

Here in Sleepy Hollow Country we are all too familiar with out-of-towners sweeping in to school us simple, unsophisticated yokels. A fellow named Washington Irving literally put us on the map with a short story about one such Ichabod Crane. In a twist of irony Irving himself was beset posthumously by a host of Ichabods, from local poet Minna Irving who was no Irving but trafficked off the famous author’s name, to the subject of this article, John Henry Titus whose use of the title “The Bard of Tarrytown” seems an unblushing attempt to trade on Irving’s reputation as a major figure in American literature.

Contents

Early Life of John Henry Titus

Titus was likely born February 1, 1860 in the village of Jefferson, Ohio, county seat of Ashtabula County, one of about ten children of William Knapp Titus and Mary D. Tallman Titus. His village of birth remained constant throughout his long life, but Titus regularly moved around his year of birth to suit the moment. In fairness to Titus, the 1860 United States Federal Census generated a little confusion by recording his age as 4 1/2 while listing year of birth as 1859. By 1870 and 1880 he was recorded as 10 and 20, respectively, pretty well setting his year of birth at 1860.

In 1880, aged 20, he was working in a tannery in Ohio. Two years later he married Agnes L. Tracy. By 1888 he and Agnes were living in Chicago. In the 1900 census, he and Agnes were living in Hinsdale, NY with their daughter Pearl. After 20 years married, they were divorced in 1902 at Monroe, MI.

For the next decade Titus bounced around New York State through a series of disparate jobs including editor of newspapers in Jamestown and Hinsdale, traveling poet and public speaker, proprietor of a hide and hair processing factory at Olean, and a public speaker at the Lily Dale Assembly of spiritualists. During this time he appears to have periodically visited Tarrytown or at least listed it as his place of residence—even when he very clearly lived and held a job hundreds of miles away.

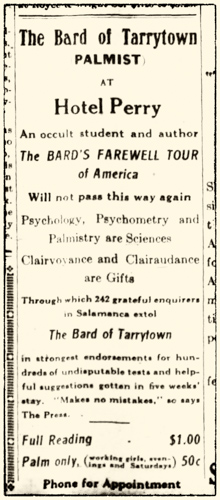

The Bard of Tarrytown, Psychic Medium

Perhaps inspired by his experience at Lily Dale, John Henry Titus launched a new career as a psychic medium. In the summer of 1913 he launched his never seen before “FAREWELL TOUR OF AMERICA” in western New York State. Promoting himself as “The Bard of Tarrytown”, he ranged from Perry down to Ellicottville and Salamanca, and then over the border to Kane, Pennsylvania. The bard offered various types of consultations including palm reading, psychometry, clairaudience and clairvoyance. Full readings were $1, palm only was 50 cents. The lesser readings were available on evenings and weekends and also to “working girls”. At a time when the average American salary was about $11/week, Titus charged a fairly steep rate.

Coincidentally during that same summer of 1913 over one hundred members of the Tallman family gathered in Perry, New York for a reunion. Descended from Tallmans on his mother’s side, John Henry Titus was listed among the attendees. He gave his place of residence as Tarrytown.

The services the Bard advertised in Salamanca, NY’s The Republican Press included “Business and Social Advisor. Unravels, Untangles and Straightens Mysteries and “Misfits” by Names and Faces and Places, gotten with Tests and Messages through Spirit and Psychic Influences.”

In The Post of Ellicottville, NY he advertised “The Bard of Tarrytown, (The Poet of the Pines) the world’s most gifted seer, palmist and medium, now at Arlington hotel, will continue his psychical readings the week out; welcoming all; and will give his famous recital and Travel Talks, closing with Platform Tests, at opera house Saturday night.”

In The Kane Republican of Kane, PA John Henry Titus pitched himself “Clairvoyant and palmist now at Kane House parlors, Home Coming Tour after 30 Years . . . Will not pass this way again. The World’s Distinguished Psychologist and most gifted seer, palmist and medium.”

Titus wore out his welcome in Pennsylvania the following year. The February 12, 1914 edition of the Brookville Republican reported: “A gentleman styling himself ‘The Bard of Tarrytown,’ who makes his living by giving psychic readings of the future, and laying bare the secrets of the coming days in matters of love, business, politics, etc., struck town the latter part of the week, and hung out his shingle at the American hotel, where he immediately attracted the usual run of suckers which such gentlemen of that ilk are able to hook. Burgess Shields, who is a wide awake official, got wind of the Bard’s business here, and he speedily informed him that he had mistaken the name of this city, and that it isn’t Tarrytown, but Move-On-Town, to all such gentry. Consequently the Bard, with grievous sighing, picked up his traps and departed hence on Tuesday morning. Score one for the Burgess!”

The Face on the Barroom Floor

After flopping as a psychic, John Henry Titus struck gold with his next idea. Somewhere around 1929 he hit upon his biggest claim to fame, the poem “The Face on the Barroom Floor” aka “The Face upon the Barroom Floor” and “The Face on the Floor”. There was a slight complication. Writer and motion picture executive Hugh Antoine d’Arcy had already published a version of the poem in 1887. Not only that, in 1914 Keystone Studios had released a short film starring Charlie Chaplin based on d’Arcy‘s poem.

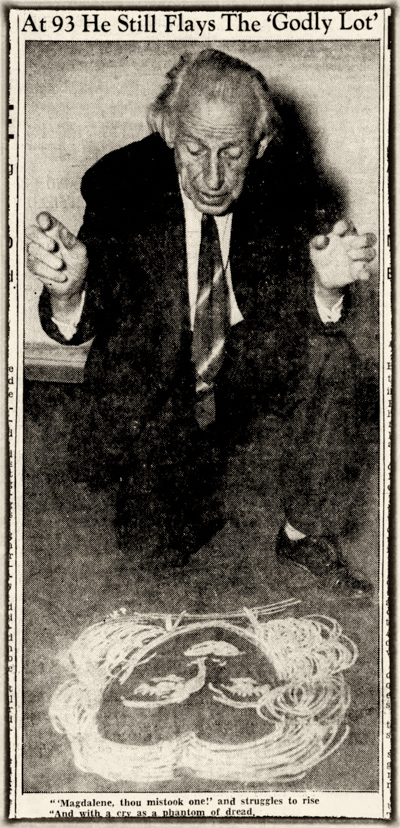

Titus was undeterred. At least 69 years old, he retained a dramatic presence—he was a tall man with a full head of white hair dangling down to his broad, squared shoulders. His physical appearance paired well with his new material. Titus ran with his new persona and for decades made a living off reciting the poem and sketching a face on any floor made available to him.

He variously claimed to have written this popular and sentimental ballad as late as 1872 and as early as the 1860s. If the 1860s timeframe were accurate the poet would have been in diapers or his early teens, depending on which birth date he gave at the time.

But back to the poem itself. It tells the story of a down-and-out vagabond entering a bar room one evening, only to meet with derision for his tattered clothes and foul stench. The other patrons slowly warm to his presence as he tells the sorrowful tale of how he arrived at this sorry condition. As a young and talented portrait artist he met and fell madly in love with a most beautiful woman. Sadly, the love of his life soon fell for the fair-haired lad of one of his paintings, one of his close friends. Betrayed by both his lover and his friend, the artist fell into depression and drink. For just another round of whisky the vagabond offers to draw the portrait of “lovely Madeline” in chalk upon the floor of the establishment. As he completes her visage, he gives a fearful shriek and falls dead across the picture.

John Henry Titus’s version of the ballad coalesced in a 1933 annotated version published with an introduction and biographical information by Elizabeth Pfleiderer. Remember that name, she makes another appearance later in this article. To bolster his claim to authorship, Titus spread word that his poem was inspired by the Old Pine Tavern back in his hometown of Jefferson. Not only that, but he himself was born in that very tavern! For a cocktail served up with lunch or dinner he would happily recite the poem and its history to anyone willing to listen.

The next year, 1934, Titus asserted that in 1872 his father was secretary to the prominent American editor, novelist, literary critic, and playwright William Dean Howells, who published “The Face on the Barroom Floor” in the local newspaper, the Jefferson Sentinel. At first blush this may seem plausible as Howells did in fact help out his own father on an Ohio newspaper. Except the senior Howells edited a newspaper 300 miles away in Hamilton, Ohio. Complicating matters, by 1872 William Dean Howells had already been on the east coast several years editing The Atlantic. Fortunately for John Henry Titus, Howells died in 1920 and was therefore unable to address the discrepancies.

By 1935 Titus had embellished his tale to include supplemental facts about the tavern and his composition of the poem. The tavern became a famous wayside inn in the days of the stagecoach. In an interview with the Associated Press on December 8, 1935 he noted “Men of quality and men of national note, judges, jurymen and lawyers frequented the ‘Old Pine Tavern…'” He asserted he wrote the original form of the verse “on bits of bark and leather in the tannery in Jefferson in which he served an apprenticeship.” The 1880 United States Federal Census corroborates his early occupation, noting the 20-year-old John Henry Titus “works in tannery.” Perhaps there was a nugget of truth to his title “The Tanyard Poet.”

New “facts” continued to gather around the old. In a May 23, 1938 interview with the United Press, he recalled that the vagabond was Robert Deleanor, a friend of Titus’s father. During the same interview, his birthdate receded to 1846, making him a strong and healthy 92 years old. Over lunch at Titus’s favorite Chinese restaurant (on the reporter’s tab, of course), he and his wife regaled the reporter with his poetic prowess—he speaking in rhyme, she noting of her husband, “He has composed more than 1,500 poems, few of which he ever wrote down.”

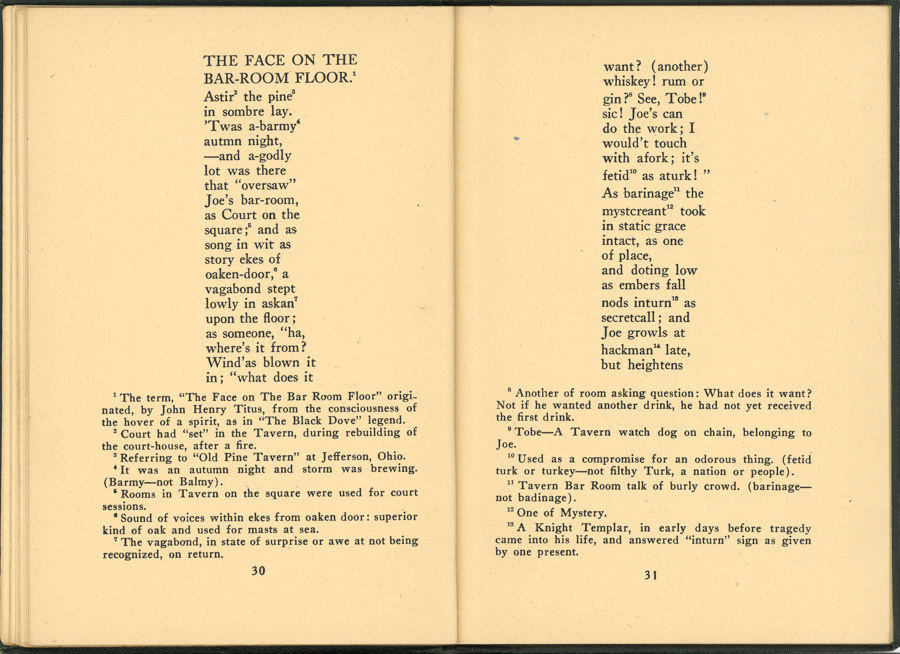

Titus’s first few lines read as follows. And yes, this almost unintelligible mess is exactly as it was printed. We have an author-signed first edition in our hands and have triple checked this excerpt.

Astir the pine

in sombre lay.

’Twas a-barmy

autumn night,

—and a-godly

lot was there

that “oversaw”

Joe’s bar-room,

as Court on the

square; and as

songs in wit as

story ekes of

oaken-door, a

vagabond stept

lowly in askan

upon the floor;

as someone, “ha,

where’s it from?

Wind’as blown it

in; “what does it

want? (another)

whiskey! rum or

gin? See, Tobe!

sic! Joe’s can

do the work; I

would’t touch

with afork; it’s

fetid as aturk!

Where John Henry Titus laid claim to the poem, Hugh Antoine d’Arcy is most often given credit for writing and publishing it in 1887. d’Arcy’s first two stanzas read

‘Twas a balmy summer evening and a goodly crowd was there,

Which well-nigh filled Joe’s barroom on the corner of the square,

And as songs and witty stories came through the open door,

A vagabond crept slowly in and posed upon the floor.

“Where did it come from?” someone said, “The wind has blown it in.”

“What does it want?” another cried, “Some whiskey, rum or gin?”

“Here Toby, sic him, if your stomach is equal to the work —

I wouldn’t touch him with a fork, he’s as filthy as a Turk.”

While scholars from time to time argue over work attributed to Shakespeare, this poem surely is not worthy of literary controversy. All we have to say of the matter is that d’Arcy died in 1925, four years before Titus publicly staked his claim, rendering him unavailable to challenge Titus. Frankly, if d’Arcy did indeed steal the lines, he delivered Titus a huge favor by cleaning up a hot mess.

Inspiration for Poe’s ‘The Raven’

Titus was a teller of tall tales and his specialty was attaching himself to famous and long dead figures who might boost his own standing without making pesky challenges to his veracity. He was an incorrigible name dropper. In a 1936 newspaper interview, John Henry Titus made the far-fetched claim that his father, William Titus, was close friends with both Edgar Allan Poe and Washington Irving. Never mind that neither author ever mentioned an association with any Titus. Perhaps to burnish his own literary legacy, the Bard of Tarrytown went even further by asserting the elder Titus was the source of Poe’s title “The Raven”.

“His father, William K. Titus, was born two years after Edgar Allan Poe, who became his life-long friend. It was on a pleasure trip up the Hudson with Poe and Washington Irving that this elder Titus prevailed upon Edgar Allan to talk about the poem he was then writing. Poe revealed the fact that the Norwegian legend of the “Blackdove” kept tugging at his consciousness for rhythmic outlet; but there was something about the title, “Blackdove,” that didn’t quite suit him—didn’t quite express the stark grief of his lines. It was then that William Titus suggested that immortal title, “The Raven,” which Poe immediately accepted.”

Miami Daily News (Miami, Florida), January 5, 1936

As was his custom in having sources known only to himself, the only reference we can find to a Norwegian legend of a blackdove or black dove is John Henry Titus’s own. Fortunately for Titus, Poe and Irving were both long dead and therefore unable to rebut his claims.

The Bard Creates Postal Service Motto

In the same 1936 Miami Daily News interview in which he laid claim to a connection with Poe and Irving, Titus also alleged he was the source of the famous unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service. He claimed his friend Elbert Hubbard, the writer and publisher (and self-described anarchist), “was instrumental in having the following excerpt from his poem, “The Litany,” placed in the General Post Office, New York.” Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.

Hubbard, however, was not on good terms with the postal service, having been convicted of circulating “objectionable” material through the mail. Further, he had perished in the sinking of the RMS Lusitania 21 years earlier and was therefore unavailable to the Miami Daily News‘s fact checkers. The USPS itself attributes the unofficial motto carved into the face of Manhattan’s former main post office to a slightly earlier piece of writing, one which first appeared around 430 BC, more than 2200 years before the birth of John Henry Titus. Denise Varano writes on USPSblog.com: “The phrase comes from book 8, paragraph 98, of The Persian Wars by Herodotus, a Greek historian. During the wars between the Greeks and Persians (500-449 B.C.), the Persians operated a system of mounted postal couriers who served with great fidelity.”

Married a Third Time

John Henry Titus married his third wife and biographer, Elizabeth Pfleiderer, on October 18, 1944 in Baltimore, Maryland. He claimed to be 97, but when he died 3 years later Pfleiderer placed his age at 94 while Bellevue Hospital signed off on 90.

The couple were married in Elkton, Maryland by the Reverend William F. Hopkins who was identified by The Sun of Baltimore as one of Elkton’s “marrying parsons.” This phrase dates to the 1920s when the town had no waiting period between issuance of a marriage license and a wedding, making Elkton an East Coast destination for quickie weddings.

As you might expect, this booming trade attracted lots of ministers with no pastoral duties to set up wedding chapels. The Rev. Hopkins was an antique dealer in addition to running a marriage mill. The Tituses took a bus from New York to Elkton on a Monday morning and within hours were married and on their way back to New York. Elkton was something like Las Vegas without glitter or Elvis.

The newspaper also noted the emergence of a curious pattern regarding age disparity. Titus not only had a fancy for younger women, he seemed to like an age gap of at least 4 decades. “Mr. Titus’ bride, his third, the former Miss Elizabeth Pfilderer (sic), is 54, or 43 years younger than he. His second wife, who he married in 1930, was 44 years his junior.”

Going with the birth year of 1860, Titus would have been “only” 84 at the time marriage to Elizabeth.

Death and Burial

After marriage John Henry Titus and Elizabeth retired from New York to a trailer near Palm Beach, Florida. A hurricane on September 18, 1947 overturned the trailer, badly injuring the elderly poet. After abruptly moving back to New York, Titus succumbed to his injuries at Bellevue Hospital on October 19 and was buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Sadly, the Bard of Tarrytown, John Henry Titus, rests eternally in Brooklyn, not Tarrytown.

Epilogue

The earliest mention of John Henry Titus in Tarrytown is a March 6, 1906 news article in The New York Age regarding church services in the village. “The literary [club] of the Shiloh Baptist Church was well attended last Wednesday evening. Mr. John Henry Titus was present.” After that his use of a Tarrytown residence appears less a matter of fact than an attempt to associate himself with the village from a distance. For instance, the “personal mention” column in the October 12, 1909 edition of the Jamestown Evening Journal noted “John Henry Titus, the wellknown lecturer, passed through Jamestown Monday on his way to his home at Tarrytown, N.Y.” A month later the same newspaper, in the same column, said “John Henry Titus and daughter, Miss Pearl Titus, have returned to their home at Hinsdale, N.Y., after visiting Mr. and Mrs. Thorp Williams for a few days.”

Other than these and the Tallman family reunion 1913 news article, John Henry Titus is conspicuously absent from Tarrytown, New York. If only in the village fleeting moments, if at all, why call himself the Bard of Tarrytown? We surmise he intended to attach himself to the reputation of Tarrytown resident Washington Irving, whose influence on American literature was still high during Titus’s formative years. This is evident in Titus’s attempt to associate his own father with both Irving and Edgar Allan Poe.

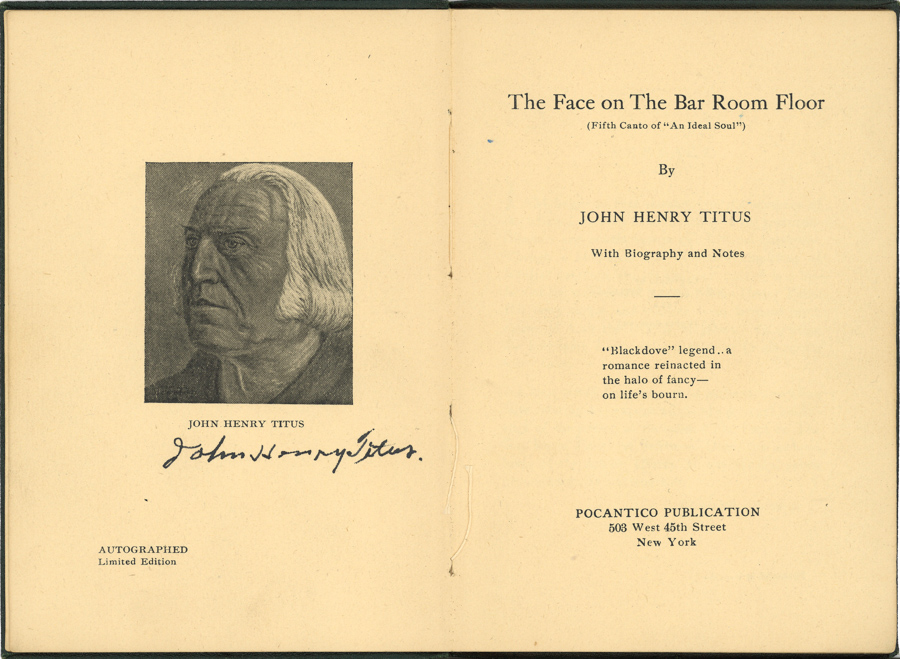

Titus’s collaboration with Elizabeth Pfleiderer on the 1933 annotated version of “The Face on the Barroom Floor” also attempts an Irving connection by issuing the slim volume under the name Pocantico Publication, 503 West 45th Street, New York, NY. This four-story brick walkup in Hells Kitchen surely was not the location of an imprint of a New York publishing firm. The book was almost certainly published privately. Borrowing the name of the Pocantico River from Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” sure seems an attempt to wrap himself in the reputation of the famous author.

Although he claimed to have written more than 1,500 poems across his lifetime, the only other known published book of his poetry is described in an obscure catalog at the New York Public Library. Titled The Bard in verse. War is Hell, and others, authorship is listed as “John Henry Titus, the bard of Tarrytown-on-Hudson”. It was published by Pocantico Colony in 1916. We have not yet located a copy.