The Ghost of Estherwood

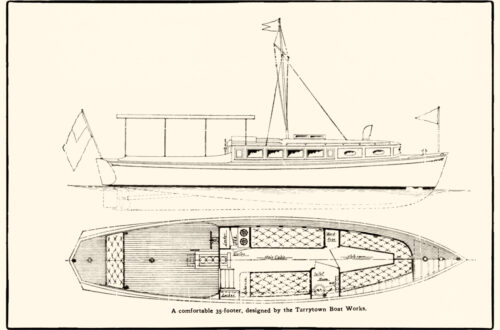

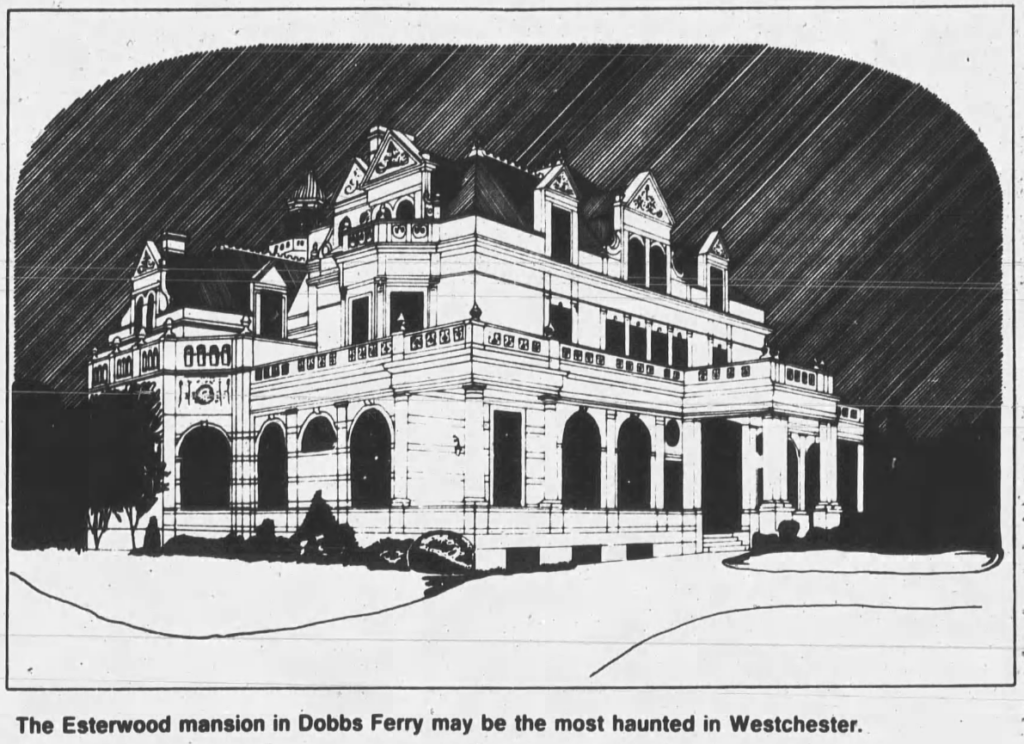

Just a few miles south of Sleepy Hollow—where ghost stories practically grow on trees—you’ll find the Masters School, a private co-ed institution with a knack for blending academics and a dash of the supernatural. Its sprawling 96-acre campus in Dobbs Ferry, NY, is home to Estherwood, a 19th-century Gilded Age mansion built by James Jennings McComb for his second wife, Mary Esther Wood. And while Mary’s been gone for over a century, rumor has it she’s still hanging around, giving us the latest entry in our paranormal playlist: the ghost of Estherwood Mansion.

J.J. McComb wasn’t just a man of wealth; he was a man of clever patents—specifically, a cotton-baling device that earned him a fortune. After leaving the Midwest for New York, he turned his money-making talents to real estate, snapping up apartment buildings around Central Park. When it came time to build his dream home, McComb picked Dobbs Ferry—a perfect choice since his daughters were enrolled at the Masters School. Estherwood became the family’s lavish countryside retreat, dripping in Gilded Age grandeur.

After the deaths of J. J. and Mary Esther, the school stepped in and added the mansion and carriage house to its campus.

Contents

Back to the Afterlife

The 1980s were like a cosmic blender set to “chaotic genius.” The Berlin Wall came crashing down, personal computers booted up for the first time, and genetically modified crops were born (because regular corn just wasn’t cutting it anymore). Meanwhile, the AIDS epidemic cast a dark shadow, MTV exploded onto screens to declare, “Video killed the radio star,” and the Internet quietly raised its hand and said, “Hi, I’m gonna change everything.” Video arcades were huge, cassette tapes were massive, and hair? Hair was so big it had its own gravitational pull.

For reasons as mysterious as a ghost’s mixtape playlist, the 1980s were either a boom time for Estherwood’s resident specter or just a golden age for ghostly gossip in the news. Either way, buckle up your paranormal leg warmers, because we’re about to moonwalk this ghost through the decade of big hair and bigger hauntings.

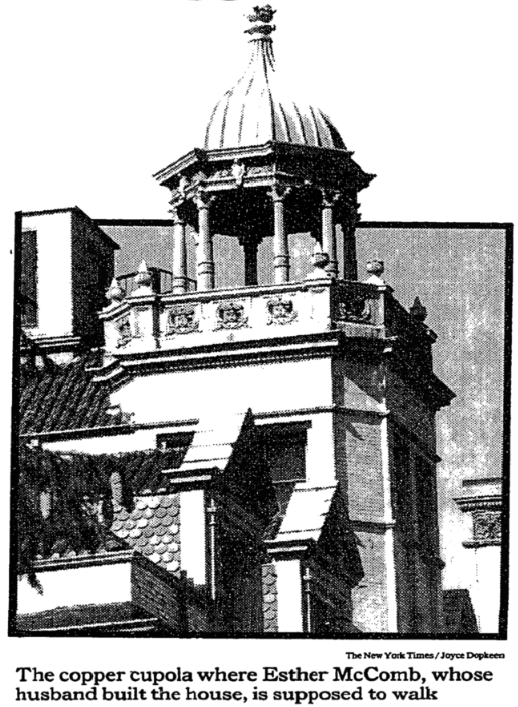

The ghost of Mary Esther Wood McComb sashayed into the 1980s spotlight with a dramatic debut in The New York Times on October 17, 1982. The article covered a proposed historic district in Dobbs Ferry, featuring a cast of sprawling estates and one star of the supernatural kind. Among the properties was Estherwood, a “chateau-esque” masterpiece decked out with turrets, chimneys, and a copper cupola. Naturally, this is where Esther McComb’s spirit reportedly likes to strut her spectral stuff.

Sweeney’s Totally Tubular Hunt for the Ghost of Estherwood

On November 13, 1983, the Herald Statesman of Yonkers decided to get spooky and ran a piece titled “Tracking ghosts who haunt homes on the Hudson River.” Reporter Michael Sweeney hit the ectoplasmic nail on the head with this gem: “That ghosts have a tendency to haunt stately old mansions rather than any old pre-fab on the block is understandable. After all, they always have had good taste in architecture.” And honestly, who can blame them? If you’re going to spend eternity pacing back and forth, it might as well be in a house with turrets and a ballroom instead of shag carpeting and popcorn ceilings.

Sweeney wasn’t done ghost-hunting yet. He roped in two members of the North Shore Preservation Society, Monica Randall and Gary Lawrence, who were deep into writing a book—working title: Phantoms of the Hudson Valley. Because nothing says “scholarly pursuit” like cataloging spectral roommates. The duo had just wowed the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society with a slide show (hey, it was the ’80s—film cameras and Kodak carousels were cutting-edge tech) featuring their research, which included the ghostly goings-on at the nearby Estherwood mansion. Turns out, even ghosts can land a spot in a PowerPoint precursor.

Sweeney didn’t hold back, declaring, “According to Ms. Randall, the house may be the most haunted in Westchester.” That’s a bold claim in a county where every third mansion seems to have its own spectral mascot. Randall cited reports spanning the entire century of a woman in white drifting through Estherwood like it was her personal runway. A ghost with a flair for consistency? Color us intrigued.

But wait, there’s more! Randall and her partner unearthed a spooky little relic in the attic of another mansion on the property: a letter on “Esterwood” (sic—because spelling is for mortals) stationery. It was from a young child named Beth, who begged her “dearest mommie” (apparently ghost sightings require posh penmanship) to whisk her away from the house because, surprise surprise, she’d seen a ghost. Honestly, Beth, same. We’d be booking it to Grandma’s too.

Who You Gonna Call?

By July 15, 1984, Estherwood had hit a high note—literally—when The New York Times’ Westchester Guide section spotlighted the Estherwood Summer Music Festival at the Masters School. This classy mash-up of music school and concert series brought together faculty from Juilliard and the Masters School, proving once again that haunted mansions and fine arts go together like Bach and harpsichords.

While hyping the mansion’s jaw-dropping grandeur, the school’s director of development decided to toss in a shout-out to Estherwood’s ghost. Coincidence? Probably not. Ghostbusters had just premiered a month earlier, and suddenly everyone wanted their own spooky sidekick. Esther, this might’ve been your big chance to snag a cameo.

”’They say that the ghost of Esther Wood occasionally haunts the place – she committed suicide,” said Carl Zimmerman, director of development at Masters. ”But she must be a genial ghost . . . the mansion is used for faculty housing and no one has been scared off.”’

-The New York Times, July 15, 1984

Spooky Sites: Randall’s Ghostly Chronicles

By October 30, 1987, Monica Randall—now rocking the title of Director of the North Shore Preservation Society—was back in the ghostly gossip column, this time chatting with a Gannett Westchester Newspapers reporter about Westchester County’s spookiest spots. Naturally, Estherwood made the list. Randall revisited the tale of the ever-glamorous ghostly woman in white, who had been popping up at the mansion since the early 1900s.

Randall brought the drama, recounting how the McCombs hosted lavish musicales in the mansion’s music room every Sunday. The twist? She became convinced “that her husband had fallen madly in love with a young musician. She was not a young woman anymore . . . She took the silk cord from her dressing gown, tied it to the stairs and hanged herself.” Not one to age gracefully—or let go of a grudge—Mary Esther staged her grand, tragic exit with theater-worthy flair.

Present-day Mrs. McComb, the reporter observed, has taken up a slightly less dramatic hobby: strolling the stairs with a candelabra in hand, apparently checking on her ghostly children.

Even the school’s dean of faculty weighed in, dryly noting, “Sometimes the faucets go on by themselves, mysteriously, so I figure the ghost is taking a bath. But if you have a vivid imagination, you can embroider anything according to your fancy.” Believe in the ghost or blame the plumbing—it’s your call.

The ghost of Estherwood is reputed to walk the copper cupola on the mansion’s tower.

Blurred Spirits and Broken Shutters

As the 1980s prepared to ride off into the sunset, the ghost of Estherwood wasn’t about to let her spotlight fade. She floated her way into the March 1988 issue of The Ferryman, the newsletter of the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society. Tasked with photographing stained glass around the village for an exhibit, photographer Evelyn Fitzgerald had spent an “exciting” winter of 1987-88 snapping shots of historic churches and homes. Sounds charming, right? But wait—plot twist!

“And then,” Fitzgerald recounted with dramatic flair, “there was the ghost at Estherwood, the National Register-listed 1896 mansion at the Masters School . . . They say the ghost of Esther herself walks there. I’m sure it was the ghost who prevented me from getting a clear picture of the stained glass skylight in the great hall near the main staircase.” Sure, Evelyn. Blame the ghost. Not low light, old film, or a shaky hand after too much coffee. Nope, definitely the ghost.

The Estherwood Ghost Story Hits More Snags Than an ’80s Perm

As you’ve probably picked up, most of the ghostly drama surrounding Estherwood can be traced back to Monica Randall, who’s spun more twists than a cassette tape on rewind. But like every good 1980s soap opera, her tale has a few plot holes big enough to drive a DeLorean through.

First, the timeline is shakier than a Polaroid picture. Mary Esther died on July 2, 1901—three months after James McComb shuffled off this mortal coil on March 31, 1901. So that dramatic staircase scene? Total box office flop. And the cause of death? Was it something tragic and self-inflicted, or just life being an ’80s buzzkill? According to the burial records at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Mary died of uremia caused by kidney failure. No ghostly drama there.

And here’s a plot twist: James also died from complications of kidney disease. Coincidence or spooky synergy? It’s the kind of mystery that could’ve been solved on Unsolved Mysteries if Robert Stack were on the case. What’s clear is that the McComb kidneys had more trouble than the Griswold family on vacation.

Esther’s Final Resting Place

The Rockland County Journal in its January 28, 1888 edition reported “J. Jennings McComb, of Dobbs Ferry, has purchased a plot in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery for $5,000. He proposed to erect a shaft of Westerly granite, which will be the largest and most expensive monolith in the United States.”

About 7 years later McComb settled on a different style incorporating columns rather than a monolith. Designed by architects Buchman & Deisler, construction was managed by Angleson & Co. In December of 1895, just as the final pieces were hoisted into the air, work came to an unexpected halt. The 8-ton roof stone slipped from a derrick, crushing the columns and base like eggshells. Newspapers at the time estimated the loss at $30,000 which would be equivalent to about a $1,000,000 loss in 2024.

In an interview with the New-York Daily Tribune, McComb disputed the figure, stating “The reports in the matter were much exaggerated, for $30,000 is more than twice as large a sum as the cost of the completed monument. At the same time, the monument will be almost an entire loss.”

The project was eventually completed in a combination of red and pink Westerly, Rhode Island granite and stands at one of the highest points in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery.

Got a ghost with a tale to tell? Spill the spectral tea and email us at ghost.editor@sleepyhollowcountry.com.