Bannerman Castle

“The sloop continued labouring and rocking, as if she would have rolled her mast overboard. She seemed in continual danger either of upsetting or of running on shore. In this way she drove quite through the highlands, until she had passed Pollopol’s Island, where, it is said, the jurisdiction of the Dunderberg potentate ceases.”

-The Storm-Ship, by Washington Irving

Bannerman Castle, one of the Hudson Valley’s most prominent ruins, sits like a sentinel at the North Gate to the Hudson Highlands. In Washington Irving’s short story “The Storm-Ship”, this small island marks the northern end of the domain of The Heer of Dunderberg, a Dutch goblin king who vexed many a sailing ship on its passage through the Hudson Highlands. Back then it was known as Pollepel, and still is, on navigational charts. No boater should pass up the chance to cruise around this landmark, especially at dawn or dusk when the sun casts it in dramatic shades of red and orange.

Frank Bannerman VI, a Scottish immigrant, constructed the castle over the period of 1901 to 1918 for the utilitarian purpose of housing the stock of his rapidly expanding military surplus business. The turrets and crenellations are a gesture to his ancestry. The Bannerman family maintained a residence on the island separate from the warehouses, the ruins of which are visible above the ramparts on the south side of the island.

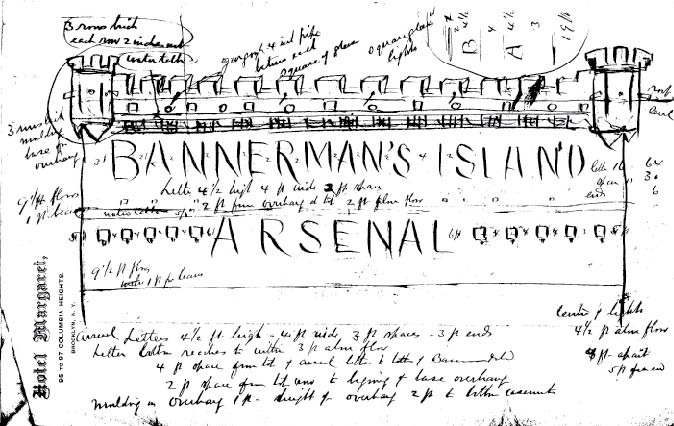

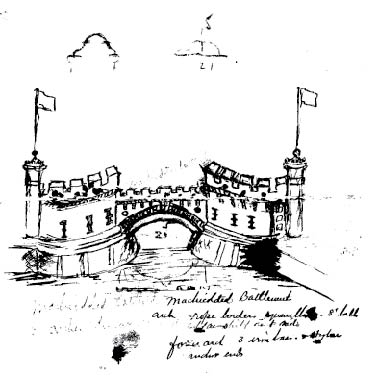

The castle itself is composed of six major sections, some of which are visible in the accompanying photos: the No.1 arsenal (figure 1, left foreground, walls mostly collapsed, its corners still stand), No. 2 arsenal (east side of the island, north of the lodge), No. 3 arsenal (figure 1, reads “Bannerman’s Island Arsenal”), the tower (figure 1, the tallest structure in the photo), the lodge (figure 2, rounded front, two-story structure at left), which served as workshop, shipping and receiving, and worker housing, and the superintendent’s house (collapsed). Also visible in the foreground is the North Gate (figure 1), the archway flanked by two turrets. All buildings on the island are constructed mainly of Hudson River red brick and concrete. Some fieldstone was used for the walls of the No. 3 arsenal, and a few cobblestones are used as ornamentation around windows and arches. The castle was built without a professional architect, to plans Bannerman himself sketched on scraps of office paper.

The remnants of the harbor breakwater are punctuated by four small towers. The South Gap Tower, one of two originals, stands midway between the island and the east bank of the river (the North Gap Tower collapsed in the 1970s). South and west, a small bridge spans a harbor entrance between the Twin Towers. Farthest west is the Margaret Tower.

For many years the Bannermans operated a retail store and mail order business from their New York City address. In its most famous acquisition, the firm purchased 90 percent of the government surplus from the Spanish-American War, both United States and captured items. As inventory grew and mail-order catalogs swelled to several hundred pages, all sorts of folks turned to the Bannerman business. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show was a client, Hollywood outfitted studio sets with Bannerman uniforms and rifles, museums and collectors came to rely on the catalog illustrations and descriptions as an aid to identifying and dating antique military items.

Even before Bannerman, the island was the location for some colorful Hudson Valley history. The island was the site of a small fortification during the American Revolution (nothing remains today) and was the eastern terminus of a chévaux-de-frise that the Americans intended to obstruct the river. It turned out the muddy bottom and tides were a bit more complicated than anticipated, and the first British ships to attempt the passage sailed over the obstacles with nary a scratch. The colonists fared better with a mammoth chain across the river under the heavy guns of West Point and Constitution Island. George Washington later authorized the construction of a military prison on the island, a project which apparently was never completed. In the nineteenth century, Mary Taft bought the island in order to curb its use by traders in bootleg liquor and other illicit activities. The island has also served as a shad fisherman’s camp.

The castle’s state of disrepair is due mainly to a massive fire in August of 1969, which gutted the buildings. That damage was compounded by the ravages of time and the elements, including a 2009 collapse of two walls of the main tower.

The island is part of Hudson Highlands State Park. Limited access is available through tours and other events organized by the Bannerman Castle Trust.

You may also view the ruins from the water, but beware of the jagged remnants of a harbor breakwater on the east and south sides of the island. These are obscured from sight between mid and high tide, but protruding metal poses a puncture hazard to all vessels. Consult navigational charts before venturing into the shallow water around the island.

The non-profit Bannerman Castle Trust has made great strides in boosting public awareness of the castle, and in raising funds for the preservation of the remaining structures. For more information contact the BCT at 845-831-6346.

Editor’s note: this article is adapted from a section I wrote for the Hudson River Water trail guidebook. It was written from the perspective of a boater.